Marketing Yourself

- Shawn Wang's How To Market Yourself Without Being A Celebrity (Link)

Graham Duncan's What's Going On Here, With This Human?

- Graham Duncan's “What’s Going On Here, With This Human?”

Self-Help Without The Guilt

- TJCX's How To Read Self-Help (Link)

How The Need For Coherence Drives Us Mad

- The philosophy of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Ethics Of Ambiguity

Preserving Habits From Covid

- Zack Kanter's Projects, Process, and the Deep Cleanse (Link)

Wooderson’s Commencement Speech

- Speech by Matthew McConaughey (Link)

Negotiating Pay

- Patrick McKenzie's Salary Negotiation: Make More Money, Be More Valued (Link) (Highlights)

We Don't Need No Education

- How To Understand Things by Nabeel Qureshi

A Walrus Opens Networth.xlsm

- 40 Lessons from 30 Years by Nat Eliason

The Inner Ring by C.S. Lewis

Highlights: http://marker.to/rmZrTG

Top Excerpts:

- Unless you take measures to prevent it, this desire is going to be one of the chief motives of your life, from the first day on which you enter your profession until the day when you are too old to care. That will be the natural thing—the life that will come to you of its own accord. Any other kind of life, if you lead it, will be the result of conscious and continuous effort. If you do nothing about it, if you drift with the stream, you will in fact be an “inner ringer.” I don’t say you’ll be a successful one; that’s as may be. But whether by pining and moping outside Rings that you can never enter, or by passing triumphantly further and further in—one way or the other you will be that kind of man.

- Corruption by the Inner Ring is subtle and gradual: And the prophecy I make is this. To nine out of ten of you the choice which could lead to scoundrelism will come, when it does come, in no very dramatic colours. Obviously bad men, obviously threatening or bribing, will almost certainly not appear...And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face—that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face—turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected... That is my first reason. Of all the passions, the passion for the Inner Ring is most skillful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things. My second reason is this. The torture allotted to the Danaids in the classical underworld, that of attempting to fill sieves with water, is the symbol not of one vice, but of all vices. It is the very mark of a perverse desire that it seeks what is not to be had. The desire to be inside the invisible line illustrates this rule. As long as you are governed by that desire you will never get what you want. You are trying to peel an onion: if you succeed there will be nothing left. Until you conquer the fear of being an outsider, an outsider you will remain. This is surely very clear when you come to think of it. If you want to be made free of a certain circle for some wholesome reason—if, say, you want to join a musical society because you really like music—then there is a possibility of satisfaction. You may find yourself playing in a quartet and you may enjoy it. But if all you want is to be in the know, your pleasure will be short lived. The circle cannot have from within the charm it had from outside. By the very act of admitting you it has lost its magic. Once the first novelty is worn off, the members of this circle will be no more interesting than your old friends. Why should they be? You were not looking for virtue or kindness or loyalty or humour or learning or wit or any of the things that can really be enjoyed. You merely wanted to be “in.” And that is a pleasure that cannot last. As soon as your new associates have been staled to you by custom, you will be looking for another Ring.

- Instead of chasing the Inner Ring: If in your working hours you make the work your end, you will presently find yourself all unawares inside the only circle in your profession that really matters. You will be one of the sound craftsmen, and other sound craftsmen will know it...But it will do those things which that profession exists to do and will in the long run be responsible for all the respect which that profession in fact enjoys and which the speeches and advertisements cannot maintain. And if in your spare time you consort simply with the people you like, you will again find that you have come unawares to a real inside: that you are indeed snug and safe at the centre of something which, seen from without, would look exactly like an Inner Ring. But the difference is that the secrecy is accidental, and its exclusiveness a by-product, and no one was led thither by the lure of the esoteric: for it is only four or five people who like one another meeting to do things that they like. This is friendship. Aristotle placed it among the virtues. It causes perhaps half of all the happiness in the world, and no Inner Ring can ever have it... To a young person, just entering on adult life, the world seems full of “insides,” full of delightful intimacies and confidentialities, and he desires to enter them. But if he follows that desire he will reach no “inside” that is worth reaching. The true road lies in quite another direction.

The Arc Of The Practical Creator

Intro and importance

- Creativity is important because it’s about agency!

- But creativity has been is imbued with impractical or whimsical connotations and relegated to art, music, writing. That’s how we think of as creatives (I think trading is deeply creative)

- Creativity is about agency Creativity is subjective. A physician may regard her role as a deeply creative endeavor in the same way that a painter would for his... Creativity has more to do with the authentic desire to express, and less to do with the art form itself. For example, it’s tempting to call a painter a “creative person,” but it all depends on why he paints. If he does so because his mother is a famous painter that expects him to carry on the family name, then painting is not a form of creative expression for him. It’s a job.

- The lesson we internalize early: creative expression is often used as a gateway to something more practical, and is rarely accepted as something practical in itself

The real reason they wanted us to take piano lessons was for developmental purposes. If we learned the piano, that would be helpful for our cognitive development, which in turn would better position us toward the actual careers they’d prefer us to have.

This is why parents will rush to place their kids on long waitlists for art and music programs, but won’t encourage them to become artists or musicians as they age. It’s as if creative expression is useful for its ability to create connections between young neurons, and once that purpose has been fulfilled, it becomes an obstacle that gets in the way of viable career paths. With this view, the arts are utilitarian at best, burdensome at worst.

- The internet made creativeness, your uniqueness an asset not a liability. Without gatekeepers and with more creator-friendly tools were introduced into the landscape, it expanded your ability to make money doing something you truly cared about. The internet enabled a vision where creativity and practicality were directly correlated. The more effort you put into your creative output, the greater the practical benefits would be. This represented a big flip in the way things traditionally worked.

Reality

The beginning:

- Here’s the harsh reality of any creative endeavor: in the beginning, no one cares. Every creator requires a balance of intrinsic motivation and external validation, but you’ll have to accept that the external piece will be missing at first.

- How will you manage the fact that you won’t be making any money from this? And without money, how will you cultivate the resilience to keep going?

- Money affords you the privilege of having a big leap feel like a small hop, which lessens the anxiety that may surround your entry into any creative endeavor. Patience is only possible when you have the requisite headspace to cultivate it, and having your financial needs covered is absolutely critical for this.

The Arc Of The Practical Creator

Prioritize money

In the first stage of the arc, you need to focus on building wealth. You’ll need to put practicality ahead of creativity, and have a job that reliably puts money into your bank account, which you can then save or invest.

A Practical Creator doesn’t view a boring job as a dead-end endeavor, but as an active patron of their creativity.

In the same way that wealthy families support the financial needs of their favorite artists, the same could be said about you and your employer. You exchange your time for money, which is then used to purchase the clarity of attention you can invest into your creative work.

.

The key to viewing your employer as a patron of your art, however, is contingent upon one important thing: When you’re in this first stage, you must rigorously work on your creative endeavors after your day job responsibilities. This is an absolute must. If every day consists of coming back home after work and then relaxing until you sleep, then you’re deluding yourself into thinking that this job funds your creative aspirations. The truth is that you don’t want it enough, and this boring job is not a patron for your art – it’s your actual career.

A Practical Creator doesn’t use the day job salary to buy everything they want, but saves as much of it as possible. They understand that every dollar saved today represents the freedom to create tomorrow. Patience is about learning to live with less, as this allows you to build up a bank account balance that could be later exchanged for agency.

The Leap

Eventually, you have fiscal certainty in the form of your savings, but on the other, you have fiscal uncertainty in the form of your creative endeavors.

Not making the leap:

If you believe that leaving your job will result in overwhelming anxiety (regardless of how much you have saved), then perhaps the wise move would be to continue doing what you’re doing. Spend most of your day building wealth, and just some of it on your craft. However, if you’re in a position where you hate your job , you must accept this harsh truth: You are trading away your creative potential for fiscal security. There’s no nice way to put it. Anyone who spends a majority of their working life in an unchallenging environment cannot cultivate the clarity of mind required to bring out the best in themselves.

Making the leap

This leap can take many forms: Perhaps you quit your job to grow yourself as a solo creator. You take a huge pay cut to switch to an industry that better suits your curiosities. Regardless of what the situation is, you’ve made a conscious choice to go against the grain of social expectations.

At this point, you will feel the conflicting feelings of relief and tension. Relief from making a difficult decision, and tension from having to navigate the consequences of that decision. And when it comes to Stage 2, there will be a lot of tension you must sort through, as this is when the current of doubt is at its strongest.

When you’re pursuing something that is entirely aligned with your creative ambitions, it will largely be perceived as irrational. Your pursuit will be viewed through the lens of what is already known (ie stable employment with regular pay). Anything that doesn’t fit in with that mental model will seem foreign, and in some cases, even silly.

And you know what?

They’re right.

It is impractical to choose uncertainty over certainty. It does boggle the mind to opt for volatility over stability. Any move that goes against the current of expectations is alarming, and the tricky thing is that you know it too. You understand the risk associated with choosing intuition over rationality, and the opportunity cost that comes with it.

The Great Plateau

This is the flat place in the arc where you’re actualizing your creative potential, but are not seeing the practical results of that effort. The customers aren’t pouring in, the audience isn’t growing, people don’t seem to care. The energy invested doesn’t align with expected outcomes, and this situation is rightfully concerning.

But here’s the good news:

This is perfectly normal.

Why does it feel concerning?

Throughout our upbringing and our time in the educational system, we are taught that an expenditure of effort leads to an immediate reward. If you clean your room, you’ll get to have pizza for dinner. If you study hard for an exam, you’ll get a good grade. If you have a great interview, you’ll get that great job. And so on. The causal chain linking effort and reward is perpetually reinforced in our most formative years, which carries with us well into adulthood.

The issue is that this chain breaks down when we want to walk our own paths.

When you direct your attention to your personal curiosities, there’s no immediate reason for society to value that. Society only values what it already knows and wants. Companies offer salaries because they know exactly what to expect from their employees, even if it takes a while for them to contribute that value. But as a creator following your own interests, you alone are responsible for cultivating the value of your pursuit, and then convincing others of it through the delivery of your work.

This means that a significant time delay must be introduced between the expenditure of effort and the arrival of rewards. This goes against everything we’ve been conditioned to experience, so we often give up on our creative pursuits well before they’ve had the required time to catch people’s attention.

The key is to remember that silence is normal, especially in the early stages. And the more you can internalize its normalcy, the greater your resilience will be in pushing ahead without looking back.

How much of this delay between effort and results can you handle? How do you know that silence is indicative of unrealized good outcomes, or if it’s actually a reliable signal that you should quit?

There’s no clear answer here, but the way I parse through this conundrum is through two lenses:

(1) Your pool of resources

If you’ve run out of money, then patience is a luxury you can no longer afford. In this case, you’ll have to trade in your creative freedom for practical security, which translates to getting a job you’d rather not have in order to make money.

This represents a move back up the lefthand side of the arc, placing you in Stage 1 again. This doesn’t mean you’ve quit, nor does it imply reversion. It just means that you can no longer dedicate your full attention to your creative endeavor. If anything, your commitment to it may even be stronger because now you have an imposed limitation on your freedom.

What matters is whether you interpret this change as empowering or demoralizing. And whichever one you choose will determine your chances of future success.

(2) Your sense of progress.

The tricky thing about patience is that you often don’t know if it’s a wise or foolish thing. It’s wise if it eventually pays off, and foolish if it doesn’t.

If the external validation piece is low, you have to use your inner judgment to determine if you’re improving. Read something you wrote a while ago, and compare it to something you published recently. Does that old piece make you cringe a bit? Good. That’s a clear sign of progression.

The other thing to consider is the texture of silence while on the Great Plateau. For example, if the silence you’re experiencing is total (meaning that no one engages with your work), and it has been for an entire year, then that’s a reliable sign that this path isn’t for you. If you can’t get 20 people (outside of your loved ones) to care after a year, it’s hard to see how that will change in the subsequent one.

But if you’re experiencing periodic breakthroughs in silence, that’s a different story. Perhaps you sent your stuff to a creator you respect, and she encouraged you to keep going. Or you notice that a small but loyal following is developing with every piece you publish. This is a different kind of silence. It’s silence in the sense that your efforts still don’t align with the results, but it’s a signal that you’re headed in the right direction.

In this case, patience is your greatest asset.

When determination, patience, and progress blend together, something amazing happens. The shape of the Great Plateau begins to change, and what was previously the flatness of despair shifts into an incline of hope. People really start to care, your audience regularly reaches out, and a viable career path emerges.

Navigate the Creative Career

So when we think of the word “career,” we naturally frame it in the context of tradition. We think of predictable cadences of work with predictable deposits of money, following a path that culminates in a predictable position of high standing. And most importantly, all this is determined by the culture and structure set by our employers.

But when it comes to your creative endeavor, you set the tempo to everything. You determine when it’s the best time of day to work, you choose when to respond to emails, and you decide how you want to build your audience. This sense of total agency bears little resemblance to what a career is supposed to look like, so it could instead feel like a serious hobby.

But if you’re in Stage 3, here’s the reality: Your craft is en route to practicality, which by definition, makes it a career path.

We often think that you have to be an established creator to justify a creative career. But no one thinks that you have to be the CEO of a company to justify your career there. No, a career begins at the entry-level, from the moment you get compensated and recognized for your capacity to solve problems. If those conditions are satisfied (at whatever scale) and you are serious about improving yourself as a creator, then you have a career.

Once you accept this, you’ll feel deeply empowered. The leap in commitment that occurs when you refer to a hobby as your career is the same as when a love interest becomes your life partner. In the same way that a marriage consolidates your networks into a united whole, every node of your creative life will be assimilated into your identity. There’s no choice but to take your creative endeavor more seriously, and you will invest the focus and rigor required to proudly refer to it as your career.

If you can cultivate this mindset while progressing forward, it’s only inevitable that the results will one day pour in. You’ll be able to convert the attention you attract into a flow of money, which allows you to invest more of your energy into this craft. A flywheel effect begins to form, and once it’s in motion, the practicality of your endeavor will become readily apparent.

In this final portion of the arc, the great gift you are given isn’t necessarily money, but confidence. Money is a surrogate for trust. This is why money is the ultimate form of external validation. Whereas any casual observer can appreciate your work, only a believer will invest her hard-earned resources into it. And when you see that there are many people who believe in you this way, then you’ll be empowered to bring out the best in yourself.

Paradoxes

Staying confident but not arrogant

A big part of the creative journey is understanding that there is no finish line. Even if you reach the heights of success, you know that there is still more room to grow. That’s because your potential is not actualized through people telling you that it is. It can only be actualized through an internal commitment to improvement, which is perpetual because we humans have the ability to recognize our inherent flaws.

The key is to divorce the allure of external validation from the commitment to internal growth. That no amount of money or praise is a signal that you’ve reached the promised land. That so much of what makes the creative journey fulfilling is humility, and that embracing uncertainty is what allows you to forge onward.

Are you a malleable beginner, or a hardened veteran? In other words, do you optimize for growth or for preservation? [or in my opnion balancing explore vs exploit]

Do you optimize for growth or for preservation? It’s often said that successful creators hustle hard at first, and then slow down later. That’s because growth requires you to open up many decision trees to see what works, whereas preservation closes them to cultivate clear judgment.

In this final stage of the arc, grow your curiosities, but preserve your attention. Cultivate a beginner’s mind for the things you want to learn about, and the things that expand your intellectual horizons. Let your inner child roam free. Learn things for their own sake, and not for their utility.

But when it comes to actually creating and making decisions, take your time. Use your hard-earned wisdom to your advantage, and slow down to give yourself the space to think. Remove everything that acts as a roadblock to your greatest asset, which is the attention you dedicate to creating.

This is where money acts as a useful tool. You can hire people to help manage the decisions that you no longer want to make. You can purchase the services required to automate the logistics you don’t want to think about. A Practical Creator understands that money’s great gift is to give you freedom over your attention, which is why they always reinvest their earnings back into their endeavors or businesses.

It’s this winning combination of intellectual growth and attentional preservation that allows you to remain on the right side of the arc. You continue expanding your desire to learn, while also reducing the many pulls of your creative focus. Your intellectual inputs increase, while your attentional demands decrease.

And by keeping this balance, your creative endeavor will retain its practicality for a long, long time.

The unifying virtue: patience

Patience has 3 textures, each have different relevance depending on the stage

- Stage 1 patience = tolerance You’d rather not spend 8 hours at a job you don’t care for, but you realize what it enables you to do. It gives you the financial breathing room required to work on your craft on the evenings and weekends, and allows you to endure the delay in outcomes. So instead of despising the job, you can embrace it as your patron and tolerate the shortcomings that accompany it. As long as you’re diligently working on your craft in your free time (which is an absolute must), you can be thankful for the fact that you have a job that affords you that creative headspace.

Gratitude for the undesirable is what defines patience here.

- Stage 2 patience = resilience the pace of your effort will not be aligned with the delivery of results. There will be silence, disappointment, broken expectations, and other variations of those unpleasant things. But the key is to remember that they are normal parts of the Great Plateau – not anomalies. As long as you’re monitoring progress and are attuned to small signals of external validation, you can accept that the fruits of your labor will arrive long after the seeds are sown. The reframing of silence is what defines patience here.

- Stage 3 patience = balance You have confidence in your abilities, but realize how quickly that could transition into arrogance. You want to freely explore your curiosities, but also understand how important it is to slow down and cultivate clear judgment. You finally have money to spend, but know that the sustainable move is to reinvest it back into your endeavor. As long as you’re aware of the equally poignant truth that rests on the other side, you can cultivate the wisdom required to make your creativity an infinite game. The acceptance of contradictions is what defines patience here.

Wisdom

Every stage will be challenging, and that’s the point.

Creative endeavors are inspiring because the scope of the problem often feels bigger than your capacity to solve it. But because you find that problem so worthwhile, you’re willing to put in the effort required to provide the best solution possible. Through this process, you become a more capable person, which allows you to address more worthwhile problems in turn. It’s this beautiful cycle that gives you a sense of purpose and meaning in how you spend your time and energy.

So regardless of which stage you’re in, understand that there is no easier or harder. There is just challenge. And the only way to cultivate a healthy relationship with challenge is to develop the patience required to manage it properly.

How Will You Measure Your Life by Clayton Christensen

On how Clayton responds to advice-seekers…

When people ask what I think they should do, I rarely answer their question directly. Instead, I run the question aloud through one of my models. I’ll describe how the process in the model worked its way through an industry quite different from their own. And then, more often than not, they’ll say, “OK, I get it.” And they’ll answer their own question more insightfully than I could have.

On remembering why you do something at all…

Over the years I’ve watched the fates of my HBS classmates from 1979 unfold; I’ve seen more and more of them come to reunions unhappy, divorced, and alienated from their children. I can guarantee you that not a single one of them graduated with the deliberate strategy of getting divorced and raising children who would become estranged from them. And yet a shocking number of them implemented that strategy. The reason? They didn’t keep the purpose of their lives front and center as they decided how to spend their time, talents, and energy.Had I instead spent that hour each day learning the latest techniques for mastering the problems of autocorrelation in regression analysis, I would have badly misspent my life. I apply the tools of econometrics a few times a year, but I apply my knowledge of the purpose of my life every day. It’s the single most useful thing I’ve ever learned. I promise my students that if they take the time to figure out their life purpose, they’ll look back on it as the most important thing they discovered at HBS. If they don’t figure it out, they will just sail off without a rudder and get buffeted in the very rough seas of life.

Not everything that matters is good at giving you prompt feedback. If you fail to appreciate this, you chase what’s easily legible at the cost of things that are hard to measure.

Allocation choices can make your life turn out to be very different from what you intended. Sometimes that’s good: Opportunities that you never planned for emerge. But if you misinvest your resources, the outcome can be bad. As I think about my former classmates who inadvertently invested for lives of hollow unhappiness, I can’t help believing that their troubles relate right back to a short-term perspective.When people who have a high need for achievement—and that includes all Harvard Business School graduates—have an extra half hour of time or an extra ounce of energy, they’ll unconsciously allocate it to activities that yield the most tangible accomplishments. And our careers provide the most concrete evidence that we’re moving forward. You ship a product, finish a design, complete a presentation, close a sale, teach a class, publish a paper, get paid, get promoted. In contrast, investing time and energy in your relationship with your spouse and children typically doesn’t offer that same immediate sense of achievement.Kids misbehave every day. It’s really not until 20 years down the road that you can put your hands on your hips and say, “I raised a good son or a good daughter.” You can neglect your relationship with your spouse, and on a day-to-day basis, it doesn’t seem as if things are deteriorating. People who are driven to excel have this unconscious propensity to underinvest in their families and overinvest in their careers—even though intimate and loving relationships with their families are the most powerful and enduring source of happiness.If you want your kids to have strong self-esteem and confidence that they can solve hard problems, those qualities won’t magically materialize in high school. You have to design them into your family’s culture—and you have to think about this very early on. Like employees, children build self-esteem by doing things that are hard and learning what works.

Give me an example…

The lesson I learned from this is that it’s easier to hold to your principles 100% of the time than it is to hold to them 98% of the time. If you give in to “just this once,” based on a marginal cost analysis, as some of my former classmates have done, you’ll regret where you end up. You’ve got to define for yourself what you stand for and draw the line in a safe place.

Be careful how you strive…

Once you’ve finished at Harvard Business School or any other top academic institution, the vast majority of people you’ll interact with on a day-to-day basis may not be smarter than you. And if your attitude is that only smarter people have something to teach you, your learning opportunities will be very limited. But if you have a humble eagerness to learn something from everybody, your learning opportunities will be unlimited. [Me: This is a powerful prescription to make yourself more teachable]: Generally, you can be humble only if you feel really good about yourself—and you want to help those around you feel really good about themselves, too.

His final recommendation…

Don’t worry about the level of individual prominence you have achieved; worry about the individuals you have helped become better people. This is my final recommendation: Think about the metric by which your life will be judged, and make a resolution to live every day so that in the end, your life will be judged a success.

Philosophy Has Lost Its Way by Lawrence Yeo

There’s Nothing More Real Than Your Potential by Lawrence Yeo

- The lion’s purpose, whether it realizes it or not, is to live another day. Humans, on the other hand, can decouple survival from purpose.

- The pursuit of purpose, however, is both a source of meaning and suffering. Purpose is largely tied to progress, and progress is most commonly measured in what one does for work.

- If you hate what you do for work, then you will either (1) find a sense of purpose elsewhere, or (2) use your job to fund other activities that are meaningful. If you don’t do either option for a long time, then each day will feel like a pointless slog, and nihilism will be there to greet you each morning.

- An existential crisis arises when you are faced with the question of purpose, and you have no satisfying answer. Perhaps you spent the last 10 years of your life working on something, only to find that it was all pointless. Or you achieved what you thought you wanted, only to feel more empty than you’ve ever been. A crisis of this nature asks you, “How are you going to make better use of your finite time now?”

- This is a stressful place to be, but there is a silver lining. We learn best through trial, and error is our greatest teacher. By knowing what doesn’t work, you erase many of the potential life paths that were once on your landscape.

- When you’re on a path that feels empowering, you don’t have to wonder whether or not you should keep going. It just feels right, and you know it. And herein lies the paradox: The less you have to ask about your purpose, the more you embody it. Use your curiosity to explore a path that feels foreign, and play there for a while. If the questioning of purpose grows stronger, then turn back. It’s not the right one. But if that question begins to fade, keep walking. You’re getting closer. Through it all, remember that there’s nothing more real than your potential. Oftentimes, the awareness of that is enough to keep you going.

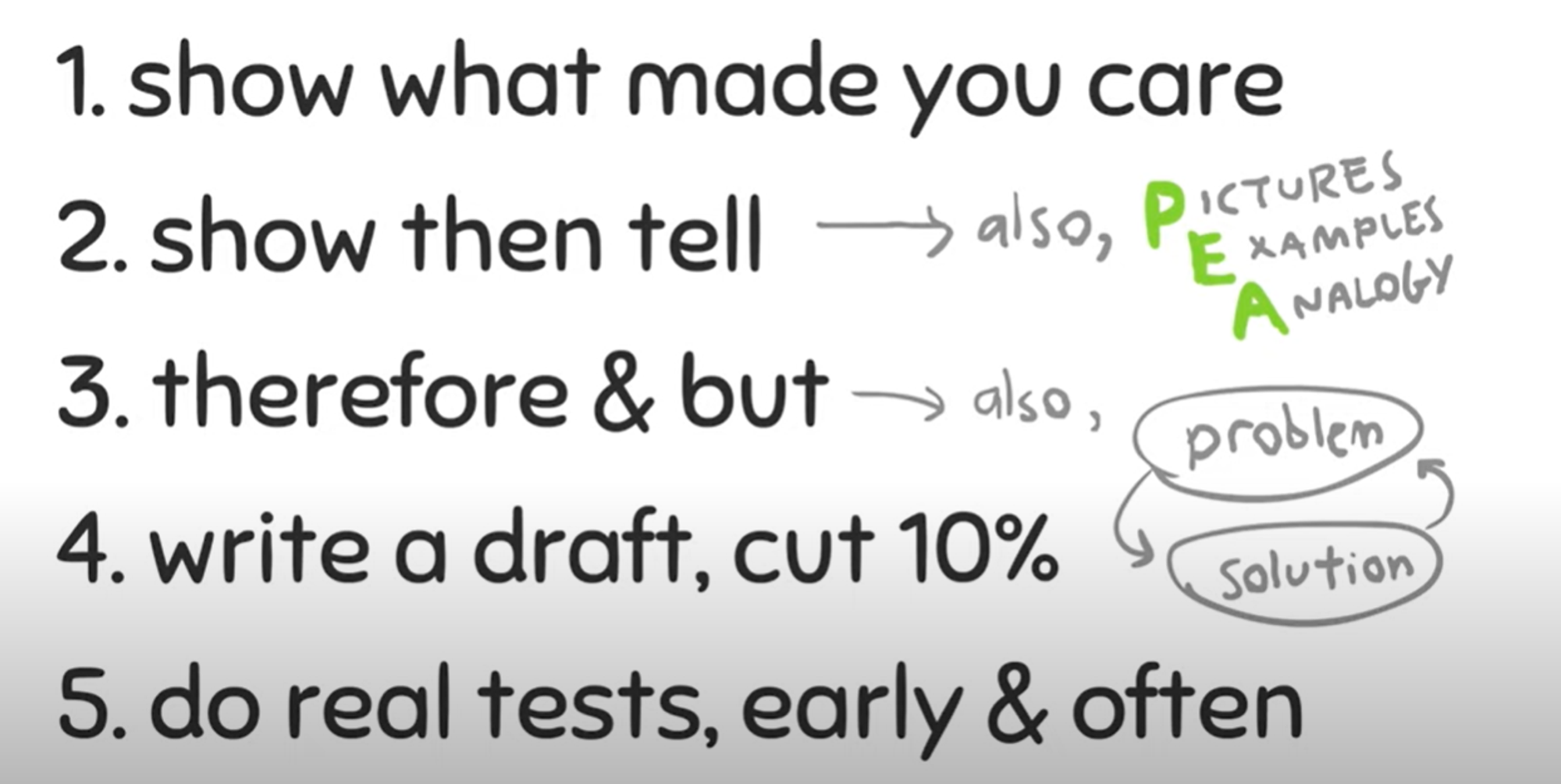

How To Explain Things Real Good by Nicky Case

The Art Of Fermenting Great Ideas by Nat Eliason

- If you want all of the ideas that pop into your brain to be clever responses to that person who was WRONG on Twitter today, then, by all means, scroll Twitter all day. If you want all your mental RAM to go towards fearing for your life over this year’s new armageddon myth, go for it. But if you want to come up with useful brain farts that move your life forward, you will have to stop feeding your mailroom dog shit. Garbage in, garbage out.

- [This next bit works for getting better at anything including relationships imo]

Removal is only the first step, though. You must replace it with the fresh juicy jalapeños you want your brain to be fermenting.

You’re probably assuming I’m going to say “read great books” or “read old stuff” here, but no, that’s not the answer. That helps shift your thinking in a more interesting direction. But it doesn’t necessarily help generate great ideas.

The most important food to constantly feed your brain is the problems you want it to be solving. These problems do not need to be grand like “solving world hunger.” Maybe one of your problems right now is what to get people for Christmas. You have to define clearly what those problems are and then constantly remind your brain to think about them. You need to be sending all-caps memos down to the mailroom fifty times a day saying COME UP WITH GIFT IDEAS!!! Otherwise, the mailroom is thinking about whether you’d rather fight 100 duck-sized horses or 1 horse-sized duck.

- [Maybe shower thoughts are shower thoughts because there's no other times when we would have such thoughts. Corollary: A good use of money is to buy time so you can be idle and have more ideas.]

Output time is creating the space and boredom for those inputs to ferment into something interesting. Staring at a blank page of your journal, opening a document to start writing, going for a (no headphones) walk with a notebook, working out without music, or sitting in the sauna. However you create bored, quite space for your brain to finally get some processing room to spit ideas out; you must create that space if you want the ideas to form.

The ways we fail at this are obvious. We never give ourselves output time because we’re terrified of silence and boredom. We need a podcast while working out. We need music while working. We keep social media up in another tab. We have notifications on our phones. We let ourselves be interrupted.

If your first response to boredom is to seek out another input to sate the longing for stimulation, then your brain never has to make shit up to entertain you. The idea muscles will atrophy and never produce anything of worth. But if you can respond to boredom by leaning into it, keeping the blank page open, and seeing what pops out, the muscle gets stronger over time.

- We all want our problems to be solved quickly, and we want to neatly move through a checklist of tasks to retain the illusion of control over our lives, but great ideas don’t seem to work like that. Sometimes you need to be exceedingly patient with them. You can’t always have all the time in the world, but when you have the space to noodle on something, take it. I’ll narrow down what I’m going to write about in this newsletter by Monday or Tuesday of the week before, then spend the rest of the week seeing what ideas pop up about the various topic ideas. By Monday, I’ll typically have the skeleton of a post fully flushed out in one of them. If I waited until Monday to start jotting ideas down, it would be much harder, and the post would certainly be much worse. So give the great ideas time to pop up. Even if you know you have weeks or months to figure something out, start priming your brain with those questions now so it has time to process them.

- Recipe:

- Find the best ingredients possible to ferment into great ideas, and aggressively prune everything you don’t want your brain to process.

- Give your brain the boredom and output time it needs to figure out what to do with that information. Don’t keep opening the jar and packing more into it.

- Finally, be patient with the process. The more you can reduce the amount of information you’re taking in, and the more boredom you can give your brain to work, the better your results will be.

Vocational Training For The Soul by Matt Bateman

In the 20th century, there are two distinct rationales for education: vocational and characterological. Putting aside how well education actually does at getting you a better job or helping you become a better person or citizen, the idea is that the core of schooling should do both.

The most obvious place to look for the economic upside of an education is in the three Rs: writing, reading, and math. There are questions as to whether the specific math that students learn is optimally practical—should it instead emphasize, say, statistics, or personal finance, or maybe even spreadsheets?—literacy and numeracy are deployed throughout the economy and do indeed comprise an unambiguously useful part of education.

Literature, history, and the arts all fall under the heading of soulcraft. Even science, the practical driver of the modern world, is not that useful as you learn it in school. A small minority of students deploy their scientific knowledge in their careers, and those that do get specialized training far beyond what you get in K-12. These things are meant to prepare you for appreciation of or participation in the human project in a non-vocational way.

These divisions are very much alive today, as people struggle to find a coherent view of what our largely dysfunctional education system is supposed to accomplish. Some criticize education for not providing more economic upside, arguing for a more practical education, shorn of classical trappings. Others defend the humanistic value of education and argue that we should spend more time on non-economic upsides. This debate cuts across K-12, higher education, and even early childhood education.

Is there a way to transcend these divisions? Is there a way to get a handle on the vocational value of education that integrates its humanistic elements, rather than downplaying or siloing them?

It is commonplace today for a person to be profoundly alienated from the entire domain of work. This is not a Marxist critique about owning one's labor, nor an aristocratic pining for a life of leisure. It is an observation that, for many people, work is a source of bitterness, not dignity. A seemingly small subset of people find meaning in work, and the rest fail to “find their passion”—a notion that is likely part of the problem—or simply resent work in a more general way.

While we still speak here and there of the value of a work ethic, the “ethic” part of this is, for us, obscure. We do not naturally see one’s personal relationship to work as a major moral issue. But it is one: the people who manage to find meaning in work are not the lucky few who land the good jobs, but the good who manage to build their souls in a certain way.

Education should offer more general value than the skills acquired on the job or in vocational training—but that general value, the soulcraft aspect of education, is not vocationally inert. It can and should nurture the beliefs and virtues associated with a life of work.

[4 ways to do this…but my favorite animates work by linking it to humans]

- The content of education should place more emphasis on the biographies that underlie it. There is no item of knowledge in education that is not the result of the work of some past human.

Second favorite:

- We should allow opportunities for real work where possible. This is especially true of older adolescents, who can get jobs—from the entry-level to technical, depending on the teen's skills and circumstances. But scaffolded opportunities can be provided for younger adolescents and elementary students to experience the reality, even the economic reality of work.

The inert child who never worked with his hands, who never had the feeling of being useful and capable of effort, who never found by experience that to live means living socially, and that to think and to create means to make use of a harmony of souls; this type of child... will become pessimistic and melancholy and will seek on the surface of vanity the compensation for a lost paradise.

And thus, a lessened man, he will appear at the gates of the university. And to ask for what? To ask for a profession that will render him capable of making his home in a society in which he is a stranger and which is indifferent to him. He will enter into a society to take part in the functioning of a civilization for which he lacks all feeling. — Maria Montessori

Books are subjectivity-merging devices, not efficient information transfer devices by Sasha Chapin

- When you read a book, you aren’t just accessing a series of propositions. You are becoming immersed in a worldview, through the rhythms of a given prose style, the facts selected and omitted, and the author’s chosen self-disclosures. Reading is hypnosis.

- A good book doesn’t usually give you a hundred pieces of valuable information…It’s like a conversation with a close friend or mentor, in which, due to a progressively cocreated intimacy, a quickly-said platitude, or a couple of relatively banal words, can have a life-changing impact.

- Often, people mourn that they are bad at retaining information. I think that it’s good that you’re bad at retaining information. Think of the information that’s out there! Professional propagandists, working through outlets official and unofficial, are constantly trying to pump you full of their memes. Many times per week, you run across advice that could totally ruin your life. Do you think “critical thinking” or a knowledge of cognitive biases could save you? Umbrellas in a hurricane. You only survive by being obtuse, by forgetting things, and by not believing what you hear. It’s only in the reading process that you slowly let down your guard, if the writer is a trained conversationalist who can make you believe that what they have to share is of value.

- This is why Blinkist sucks ass, and why I don’t generally find that serious readers I know use book summaries. It’s true that many serious readers I know will skim, or read parts of books, but this isn’t the same thing. If you’re good at skimming, you can still get a sense of a book’s atmosphere and perspective as you’re picking up a sampling of its arguments.

- Even if a book teaches you nothing, it can still provide talismanic value—reading a book about something can signify an intention to live differently. Maybe one particular book on marriage won’t make you a better partner, in and of itself. But the time spent reading it will be time spent engaging with one’s thoughts about the subject, and, ceremonially, proving your devotion to it.

- Typically, efficiently absorbing a set of facts, if they lack a rich context or greater animating purpose, is not good for much. You mostly get the impression of knowing something, which is not the same as knowing something.

- If you’re interested only in what can be efficiently slotted into your existing thoughts, you’re probably missing nearly everything.

What I Do When I Can't Sleep by Dan Shipper

Making what you like explicit is a powerful tool. It will help you articulate it to yourself and to other people. This will help you refine and make more of it.

The place to start when you’re trying to develop taste is to find and record the things you like.

Kris: I do the same thing:

This is how I use my Ineffable List when I’m writing. I’ll scroll back through it and find a sentence, a phrase, or an idea that catches my eye. Then I’ll try to fold it into whatever I’m working on. Sometimes, what I find can be placed directly into the piece. Mostly, it serves to put the equivalent of an Instagram filter on my writing voice. It pushes my language and my ideas in directions that feel inspired and interesting rather than flat and stark.

This process is effortful, tough, and manual labor. But it creates richer, more vibrant writing. Over time, with practice, it becomes more automatic. Suddenly, you don’t have to reach for your list as much because your list is inside you. You’ve found your voice.

I learned this trick when I interviewed the novelist Robin Sloan. He keeps a log of notes too that he uses to enrich and inspire his writing. It’s a list of things that have, what Robin calls, The Taste. These are ideas, quotes, and sentences that light him up, even if he can’t fully explain why:

“If I could describe fully what makes [one of these] special there’s a sense in which I wouldn’t need it anymore. The description that captures it fully, is the same as the [quote]. This whole process of note-taking is a very gradual process of me finding my way towards something.”

What Nobody Tells You by Tom Morgan

I frequently encounter people in various degrees of distress caused by being stuck or lost, mostly professionally. I offer them all a profoundly optimistic insight. I believe your present suffering is directly proportional to your future potential. I can’t see how it could be any other way. If you had no latent potential, and were content to be stuck in a mediocre life, there would be no psychological pain.

The vast majority of us start our professional lives as parts of a larger organization. This can provide us with marketable skills and necessary discipline. But it sometimes means adopting a professional persona that increasingly conflicts with your internal sense of integrity. The mask that eats your face. Too often we’re paid to stagnate, not to grow.

Contrary to a lot of self-help and spiritual literature, I’m not sure that we can travel from “corporate value” to “personal value” either quickly or easily. This is because in order to get paid to be yourself, you first need to know what your unique gifts are and then match them to what the world needs. This process often requires an intense suffering you wouldn’t voluntarily buy, even if you could find a guru crazy enough to sell it to you.

A substantial benefit of private wealth, for you or your family, is that it can provide some shelter from the storm during a transformation. As long as it doesn’t get so comfortable in there we forget to change.

“Your armor is preventing you from growing into your gifts.” Only once we’ve started to do that, I find economic value often follows. The degree to which your outer life sometimes reflects your inner life is nothing short of mystical. You always seem to have to take the first step yourself, to cross the threshold voluntarily. It’s easier to act yourself into a new way of thinking, than it is to think yourself into a new way of acting.

Once you hear the call to adventure, you have the choice of the pain of stagnation or the uncertainty of exploration. Both are impossibly daunting, but only one of them definitely ends in a literal or metaphorical death.

- From Blog to Book: How To Self-Publish On Your Own Terms by Paul Millerd

- How To Create Luck by Shawn Wang

- Happiness Is Bullshit David Pinsoff

- How To Choose The Best Note-Taking App by Ann-Laure Le Cunff

- Relationship Resentment by Khe Hye

- The Super Mario Effect - Tricking Your Brain into Learning More by Mark Rober (TED talk)

- Your Elusive Creative Genius by Elizabeth Gilbert (TED talk)

- Proof You Can Do Hard Things by Nat Eliason

- Prologue To An Anti-Affirmation Movement by Freddie deBoer

- You Need To Practice Being Your Future Self by Peter Bregman

- You and Your Research by Richard Hamming

- Attraction and Promotion by Jared Dillian

- School is Not Enough by Simon Sarris

On Writing Better: 43 Things I Learned from My Insane 2 Years of Study by Nat Eliason

Overview

- Write a Fucking Book

- It's not a series of articles

- Be simpler

- While my articles are fine being a little more technical, the book needed to stand on its own. It needed to appeal to a much larger audience

- much better to leave some detail out and upset the top 1% of people in the field who will think you dumbed it down too much than to give a complicated topic the full treatment and alienate the other 99% of readers. If they want to learn more, they can always do it after.

- Don't be TOO concise

- You have to create a book-reading experience, which is hard to do if you're still locked into your Internet concision-optimization mindset. So draw things out. Create a story around them. Play with the reader's energy. Create some tension and suspense. You know, foreplay. Not only will it make the book more fun to read, but it'll make it more memorable too.

On writing productivity

- Track where and when you write best. Experiment.

- Protect Your Subconscious…Your subconscious is incredibly smart and incredibly dumb. It will spit novel insights out of the ether as if they were shuttled to you by God, but it will spit out those insights about anything you feed it with.

- He commit to 2k words per day before allowed to do anything else (4k for editing)

- Write your way through writers block

- shitty draft is much better than an unfinished draft

- Priming! (Near technique to hit the ground running once you start writing for the day)

- Look at what you wrote yesterday (but don’t edit!)

- Look at your outline for where you want to go next

- Look at some inspiration, either a writing book or a book you want to emulate

The first thing you do when you wake up in the morning is:

Then go about the rest of your morning routine. Ideally you do this a few hours before you actually sit down to write.

Write a detailed proposal

The proposal explains what the book is about, why now is the time to write it, why YOU should write it, who’s going to read it, how you’re going to market it, etc.

This might take a month or two to do it properly. The Crypto Confidential proposal took about two months to be finished (though not working on it full-time).

But this is very, very worthwhile time spent considering how much clarity it will give you on your project.

And it might make you realize that this is the wrong book, or the wrong time, or that you’re not really the right one to write it! That’s helpful to learn too.

Outline

If you want to maximize impulsive creativity you could keep the outline concise, and only list the top ~10 major scenes that you plan to navigate through so you can figure things out along the way.

Or you could go to the opposite end of the spectrum and outline every single scene and every single beat within the scene and then start chugging through it.

Either way, you need something to keep you on track and to keep you from getting stuck along the way.

As eager as you probably are to skip to the fun writing part, investing a month or two up-front to really nail your outline is going to dramatically reduce your headaches along the way.

Outlining styles: digital or physical (paper or cards) all fine. Personal. Just know it will evolve. As soon as you start writing, you’ll realize something needs to be tweaked. That’s fine! Take a few minutes at the end of each writing session to look at your outline again and see if anything needs to be adjusted.

Story structures

Looking for some proven story structures to try to fit your book into can be very helpful for creating the initial scaffolding. It will make sure you're hitting important major points like the inciting event, the climax, the midpoint (which does not mean middle, it means when the protagonist goes from being reactive to proactive).

There's the three-act structure, a classic most people are familiar with (though not that helpful for structuring).

There are more complex ones like The Snowflake Method.

There is the 7-point Story Structure (I rather like this one).

Don't need to adhere dogmatically but useful to think of the story structure.

Scenes vs chapters

The organizing unit to focus on is Scenes, not Chapters. A scene is essentially:

A continuous period of time (no time jumps)

In one location

With a character who wants something

And the result of whether or not they get the thing

But within the scene there must also be some conflict over the character achieving their goal. And for the reasons below about “keeping a reader interested,” it must not be an easy conflict.

A chapter is just a container for any number of scenes, with the occasional summary of other details in between them. And when you can, it helps to end the chapter in the middle of a scene so the reader wants to see how it resolves.

Your book is a series of scenes that naturally flow from one to the next, with each one opening new questions and resolving them in the reader’s mind but which all service the overarching book-question they’re trying to answer.

Getting Better at the Actual Writing

- Reps

Crypto Confidential went through five drafts, and the first two were objectively bad. But I needed to do that to get the reps in to start to get good. So just be prepared for that. It’s going to take a lot of reps.

- Pick One or Two Core Skills at a Time

- There are a TON of skills you need to get better at to write a good book. Structure, story-telling, dialogue, description, scene, suspense, explanation, character-building, word choice, energy flow. If you try to get better at everything at once, you’ll get overwhelmed and not make much progress. Instead, pick one or two things and focus all of your energy there first. And ideally, pick ones that are essential to writing a good book. For me, I focused almost all of my energy on story-telling and suspense because if people are interested enough in a story, they’ll forgive other aspects of the writing being weaker.

- More Fast Drafts

- I found it much easier to improve by finishing whole drafts of the book, picking specific aspects I needed to improve on, and then doing another draft specifically targeting those things. You’ll also find, especially for your first book, that you get SO MUCH BETTER after each draft that you’re a little embarrassed by the beginning of your previous draft. That’s fine! Be willing to start fresh using the new skills you developed.

- At the core of keeping a reader's interest is creating questions in their mind that they want answered. Early on in a book, as quickly as possible, there needs to be some big question that gets planted in the reader's minds which they care enough to find the answer to

- Yes but, No and

- A character should never get exactly what they want or what they're trying to get in a scene. Instead, they either SHOULD get what they want BUT it has some unexpected consequence.

- either SHOULD get what they want BUT it has some unexpected consequence. Or they should NOT get what they want AND it should have some additional unexpected consequence. Harry DOESN'T get what he wants (the letter), AND he gets locked under the stairs. Eventually he DOES get what he wants (whisked away by Hagrid), BUT he finds out the most powerful wizard in the world might be alive and trying to kill him. Luke DOES find the droids, BUT he gets captured by the sand people. Eventually he DOESN'T defeat Vader, AND he finds out Vader is his father. This is one of those writing tricks where once you know it you will see it everywhere

- The Most Important Part of Editing is Walking Away

- your first draft is going to suck. It just is, and that's fine. And it's probably going to suck for consistent reasons. My first draft sucked because: 1)The story was disjointed and poorly paced 2)My storytelling was weak 3)I was way too confusing and in the weeds 4)My scene descriptions sucked 5)I had too many plotlines Most of that (except for number 5) could have been figured out by reading one chapter. So especially in the beginning, don't ask for feedback on the whole book. Pick an early chapter you think is your best one and show that to people, and then assume that anything wrong with it is extra wrong for the rest of your book.

- Don't Edit Before You're Done with a Draft

- Write Down What You Think People Will Say Before You Ask for Feedback

- The more you can train your intuition about what's wrong with your work, the better it will be, and the faster you'll be able to work. But you can't train that intuition without testing it against the market. So before you send something off for edits from anyone, write down what you think they'll say is wrong with it, then compare. If you think something is wrong and everyone else does, then it's DEFINITELY wrong. But there might be things you think are wrong that no one is bothered by, which could be just a small preference or a symptom of perfectionism. You might also find that everyone thinks something is wrong which you had no idea of, and that's a wonderful blindspot to be made aware of.

- Ask People What They Like When you send stuff out for edits, also ask people what they like. It might give you clues on how to make the rest of the book better.

- Readers Are Right That Something Is Wrong, But Wrong About How to Fix It

- If It's Not Painful, You Aren't Cutting EnoughPeople rarely complain that a book is too short. But often complain that a book is too long. There are going to be parts of your book that you really, really want to keep, but have to cut to make it fully focused on the main story you want to tell, or the main point you want to make. The first draft of Crypto Confidential was 100,000 words. Then I cut it down to 70, built it back up to about 100, cut it down to 90, then I thought I was done with it. But I had a feeling I could make it a little tighter to have that extra bit of confidence that more people would finish it. I went through it with a fine-tooth comb and cut another 8,000 words to get it down to 82,000.

- The last round of edits should be PAINFUL. If you're only cutting material you want to cut, you're not cutting enough.

- Don’t Edit the Draft, Make a New OneEspecially if you’re coming from article writing, it will be tempting to try to edit your draft within the existing doc. But if you do this, you’ll make fewer changes than you probably should. You won’t be going over it with a sufficiently fine-toothed comb. Instead, make an entirely new document and start from the beginning. You don’t have to type everything out again, but at least for the first few drafts, copy your paragraphs over one-by-one so you’re sure you really want to keep them as they are. The act of reading, copying, and pasting will slow you down and make sure you give each piece of the book the attention it needs.

Editing & Getting Feedback

I wrote Crypto Confidential in 5 drafts.

In-between each draft, I took three to six weeks off from the book. The first break was six weeks and they got shorter as I got closer to the finish line.

The first draft took about four months of work, but the subsequent ones all took 1-2 months. So I spent almost as much time not-writing as I did writing.

These breaks were ESSENTIAL to the editing process though. You would be amazed at what you figure out while you're not looking at the book, and when you subconscious can noodle on little problems or things you ran into. I would also use that time to study aspects of writing that I thought I was weak at, which meant that when I went back for the next draft I had a whole new set of tools I could use to improve it with.

On that note, don't waste time editing ANYTHING -- not even a misspelled word -- until you're done with a full draft.

When I finished the first draft it was about 100,000 words. The first thing I did was go back to the beginning and delete the first 30,000 of them. They were boring and unnecessary but I had to finish the book to realize I didn't need them.

If I had spent ANY time editing those words it would have been a total waste.

I'm pretty convinced this is the big bottleneck for most people with finishing a book in a reasonable amount of time. They write some, then they edit, then they write, and they edit, and it ends up taking forever to finish a draft. Don't do that. Finish the draft, then let it sit, then edit.

[Kris: I think this would be hard to do and coming up with a way to committing to not editing would be wise]

Excerpts on Slow Productivity by Cal Newport

- Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout

You can’t be busy and frenetic and bouncing off the walls with 100 projects if you’re obsessed about doing something really well. It’s incompatible with that. Now, doing something really well means you might have some really intense periods when you’re pulling something together, but it is incompatible with being busy.

- The glue is quality first

Obsess over quality. Yes, because the other two principles are to do fewer things and work at a natural pace. However, if you’re only adhering to those two principles, you’ve set up a sort of adversarial relationship with work in general. It’s as if all you’re thinking about is how to do less. You see work as an adversary. You want more variety in your pacing. You’re just trying to reduce or change work. If that’s all you’re doing, you’re building up a negative attitude towards work, which I believe is one of the dominant reactions to burnout right now in, let’s say, elite culture. It’s an outright rejection of work itself.

Orienting towards agency by Matt Bateman

A blast of perspectives, an enumeration of facets, meant to ease one’s orientation to this idea of agency. My students found them helpful, and so I offer them to you here:

- Traditional education kills agency by removing choice and interest. Progressive education kills agency by removing excellence and competence.

- Agency is rate limited by competence.

- Being trait agential usually flows from developing solid baseline competence in a handful of different domains. Like: one technical domain, one intellectual domain, one interpersonal domain, one creative domain.

- Build a shed, develop informed opinions about history, resolve your social anxiety, learn an instrument. These and like victories are the countless premises from which the conclusion “I can author my life” follows.

- Being high agency doesn’t mean being a lone wolf, it means creating your pack.

- Conversely, belonging is downstream of agency, especially in adolescence and beyond.

- There’s a common and wrong idea of agency in which it is exercised in selecting something from the menu but not in eating it. Agency is self-direction more broadly, not choice or selection.·

- Choice is big muscles, an initial lift; competence is small muscles, granular control; persistence is endurance, sustained interest. Agency is the sum of these (and more).

- Choice can offered and competence can be scaffolded. The hardest thing to solve for, the most developmentally fragile, is persistence.

- Having your own standards doesn’t necessarily mean having different standards. Living differently is a dramatic illustration of agency, not a definition of it. Being high agency can look quite normie.

- Relatedly, getting too deeply sucked into the aesthetic of being non-standard is low agency. To be reflexively non-standard is to be beholden to the standard.

- “Critical” thinking" is not higher agency than thinking. Critique is not the only way to be thoughtful, to be intentional, to form knowledge. It is one way, and a way that is often suboptimal way.

- Agency is not a natural state. Removing blockers to agency is important but it’s more important to build the scaffolding of agency, which is not there by default.

- It’s most important to think about the big things agentially—the arc of your life, relationships, work, beliefs and values—but the small things also matter. Fix small problems with low-hanging solutions. Cold? Buy a space heater. Too much TV? Make a date night.

- History, done right and with a progress bent, helps bring agency into focus. “We can’t—” —Shh. We went to the moon.

- The endurance part of agency is built first by getting joyfully lost in a task. The capacity to occasionally do things you don’t like comes in large part from developing the capacity to do things you do like. Most people never develop the latter and so struggle with the former.

- Content itself can be higher or lower agency. Teaching things historically, as having been discovered, created, established by human effort, is a high agency curricular frame. Teaching history intellectually, as driven first by ideas, beliefs, values, is high agency.

- Playing sports, learning an instrument, putting on a play, getting a job, making an app—if the education you’re offering isn’t actively helping with these and cognate modes of developing agency, then it had better not be blocking them.

- Many of the components of education thought to be low-agency are actually perfectly suited for high-agency education. Practice. Repetition. Memorization. These are good methods by which to intentionally shape your own soul.

- Agency is for everyone. It’s like honesty. It’s a virtue to be cultivated, not a lucky personality trait.

The Meaning of Life Is Absurd by Lawrence Yeo

- Dan Harmon: then every place is the center of the universe, and every moment is the most important moment, and every thing is the meaning of life.

- The questions of “What does it all mean?” and “What is my purpose?” are things we ask when we’re not plugged into this very moment. When we’re paying close attention to the project we’re working on, the book we’re enjoying, or the time we’re spending with our loved ones, then we’re not searching for meaning; we already have it.

- In this futile pursuit of escaping the absurd, nothing will ever be good enough because we are always chasing an elusive grand narrative, our overarching meaning of life. We will forever be chasing our own tails, wondering when the hell the universe will answer our individual calls for purpose.

Excuse me but why are you eating so many frogs by Adam Mastroianni

- This is an extra special type of tragedy, a tragedy that unfolds while everyone cheers. Strangling your passions in exchange for an elite life is like being on the Titanic after the iceberg, water up to your chin, with everybody telling you that you’re so lucky to be on the greatest steamship of all time. And the Titanic is indeed so huge and wonderful that you can’t help but agree, but you’re also feeling a bit cold and wet at the moment, and you’re not sure why.

- stop thinking that frog-eating is such a virtuous thing to do. A little self-discipline builds character, but too much self-discipline breaks it.

- Notice how an experiment changed the author here: As a lark, I started writing this blog. And suddenly I didn’t need self-flagellation to get work done. I lost track of time (and tomatoes), I didn’t want to take breaks, and bedtime became a disappointment because it meant I had to stop. When I’m writing this blog, I feel like that scene in Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark where Harrison Ford sticks the Staff of Ra into an underground map at the right time of day and a beam of light shines through the ruby at the head of the staff and it reveals the final resting place of the Ark of the Covenant. Which is to say, I feel like I’m in alignment with the universe, channelling sunlight, illuminating something that used to be unknown…I’m still writing those papers, but now I’m easier on myself. I no longer think there’s something wrong with me

- the “math” of success by Visakan

- No complaining by Jared Dillian