Working for Free

- Jonathan Bales' Should You Work For Free? (Link)

The Antidote To Abstraction

- Charles Eisenstein’s The Age Of We Need Each Other (Link) (Highlights)

When Smart People Have Bad Ideas

- Slatestar's Rule Thinkers In Not Out (Link) (Highlights)

Borders Are Subjective

- Slatestar's The Categories Were Made For Man, Not Man For The Categories (Link) (Highlights)

When Equality Is Cruel

- Slatestar's Parable Of The Talents (Link) (Highlights)

The Zeroth Commandment

- Hotel Concierge's The Sound Of Many Hands Clapping

Deceiving Your Kids

- Paul Graham's Lies We Tell Our Kids (Link)

The Magic for Making Quantum Leaps

- Autotranslucence Becoming A Magician (Link)

Twitter Doesn’t Kill People.

- Venkat Rao's Against Waldenponding (Link)

Which Principles Are Ok To Bribe?

- Axiology, Morality, Law by Slatestarcodex

Unpacking The Beauty Of A deBoer Book Review

Freddie deBoer's Review: Ross Douthat's The Deep Places (Link)

Keepsakes From Slatestar’s Fake Graduation Speech

Slatestar's SSC GIVES A GRADUATION SPEECH (Link)

Notes on Moloch

Slatestar's Meditations on Moloch (Link)

He Disrespected Me

Rob Henderson’s Understanding Young Male Syndrome (Link)

The Psychedelic Trojan Horse by Alexander Beiner

My highlights here

- My quick takes:

- Greed always brings the sociopaths who force Moloch on us

- The narrow interpretations of science (scientism?) is a “not everything that can be measured matters, and not everything that matters can be measured” problem

- Quote: The sacred is not there to make our lives better. It is not there to confirm our warped ideologies. It is there to shred us. It guides us to the depths of ourselves to find our own delusions and dispel them. Psychedelics were originally called ‘psychotomimetics’, because they were thought to temporarily induce insanity. It may be that going temporarily mad is the only way to see how mad we already are.

- I kept coming up against a paradox. It haunted me for months, and goes something like this: psychedelics can change our minds, but only if we’ve already changed our minds. They can transform culture, but only if culture has already been transformed. The real issue isn’t psychedelic capitalism, but the culture that selects for it. In the grips of a meaning crisis, consumer culture is adrift, purposeless, disconnected. The role religion used to play has been filled by alternatives that aren’t designed to fill its shoes. Wellness culture asks us to be well but doesn’t explain what we’re being well for. Tech utopianism bypasses the pain of existence by fantasising about transcendence. We can’t mix and match indigenous frameworks unless we come to terms with the indigenous narcissism of Western psychology. New Age thinking is a mess of self-deception and wish fulfillment. The religion of psychotherapy might bring us some peace, but it doesn’t give us an ontology. Scientific reductionism can measure our pain, but can’t help us to feel it and live with it.

Nihilist Nation by Garret Keizer

- Arguing with a nihilist is like intimidating a suicide bomber: The usual threats and enticement have no effect. I suspect that is part of the appeal for both: the facile transcendence of placing oneself beyond all powers of persuasion. A nihilist is above you and your persnickety arguments in the same way that Trump fancies himself above the law.

- If a Protestant ethic will make workers go more obediently into the factories, then capitalism will extol the Protestant ethic; but if blasphemy begins to move merchandise at the mall, then it will blaspheme to the point of making Beelzebub blush. If democracy furthers profit, then long live democracy; if democracy impedes profit, then long live Citizens United and private security forces flown in to beat back the disaster-riled mobs. In the capitalist bible, profit and loss always trump the Law and the Prophets.

- If there are no “grand narratives,” no self-evident truths, no straightforward texts, no criteria for determining artistic merit, then there is surely nothing to stop us from deconstructing such obsolete products as The New York Times and the Bill of Rights—or even, as so many academics seem obtusely unable to grasp, to deconstruct the self-evident merits of “diversity” itself? If you preach iconoclasm while dedicating a rainbow-colored stained-glass window, you shouldn’t be too surprised if somebody picks up a rock.

- Some will object that few people sporting a Make America Great Again baseball cap are going to have read postmodernist theory, so any claim of a cause-and-effect relationship here is ludicrous. No, the objection is ludicrous. It is like saying that a seabird cannot show up on a beach covered in petroleum since a seabird is obviously not an oil tanker. Culture is a highly permeable ecosystem. Mike Pence was influenced by Lady Gaga even if he couldn’t pick her out of a lineup.

- Steve Jobs’s claim of having “put a ding in the universe.” When the universe itself is fair game for dinging, can nihilism be far behind?

- This is where primal emotions and capitalist dynamism meet: in the moral deadening that comes of having few significant choices and infinite trivial ones.

- The same temptation can occur in less momentous deflations, whenever insincerity peeks from under a euphemism—whenever the “guest” turns out to be a customer. And it may be especially tempting when a culture suspicious of moral imperatives replaces them with the notion that sincerity is the highest virtue and hypocrisy the gravest fault.

- The corollary for the least capable statesmen is only too clear: In a moral universe where good and evil have been reduced to sincerity and hypocrisy, Donald Trump (the liar who believes his own lies) will always play the honest angel to Ben Franklin’s duplicitous imp.

- American nihilism is an oozing sore, but like an oozing sore it is evidence both of a malady and of a body’s desperate attempt to heal itself.

Book Review: San Fransicko by Slatestarcodex

Enjoyed watching Slatestar’s mind work thru the claims.

Just some excerpts I liked, just a matter of personal taste in the writing.

- It makes enough different claims to leave the reader feeling kind of overwhelmed. If the claims are true, then the book is great and important. If they’re false, it’s bad and damaging. I felt that the fairest way to review this book was to meet it on its own terms with deep dives into ten of its key claims.

- Overall, I’m disappointed in most of the published research on this question, which seems more interested in producing glossy brochures about funding disparities than in informing anybody what any of their numbers mean.

- Still, everyone is sure that the reason there are still homeless people must be that some Housing First opponent still exists somewhere, ruining everything with their purity-testing ways. But actually these people have already been relegated to the conservative think tanks where moribund ideas go to die.

- San Fransicko is right to call out all the people promoting it beyond what the evidence supports, but then goes on to attack it beyond what the evidence supports.

- Its claim that it saw increased drug use depends on your definition, but is misleading and not the most natural way to sum up the evidence.

- How suspicious should we be of each type of story? There will always be an extreme right tail of overly harsh sentences, and an extreme left tail of overly lenient ones. Were the 2000s really as draconian as they felt? Is the modern era really as pathetic? Or is it all just a function of who you read and what agenda they’re pushing?

- Maybe a better argument against this being true is how stable the shoplifting rates have been over time. Wouldn’t it be weird if (let’s say) a tripling of the real shoplifting rates was matched by a third-ing of the reporting rates (rather than a halving or a quartering or whatever)?

- I accept that the data don’t consistently show a spike in shoplifting. But what’s the alternative? My patient who works in loss prevention in SF stores is lying to me? The nice elderly Chinese man who sold me my last pair of glasses and chatted to me about the rampant shoplifting in his mall was lying? The San Francisco police are lying? Walgreens pretends to be concerned about shoplifting as part of a dastardly plot to close a bunch of stores for no reason? Target and CVS pretend to care about shoplifting as part of a plot to restrict their stores’ opening hours for no reason? Every big store near me has suddenly gotten a security guard at the front as part of some corporate-sponsored jobs program?

- Maybe the conservative narrative that soft-on-crime San Francisco must be experiencing rising crime rates took on a life of its own. Maybe it infiltrated not just the usual suspects like the SF police unions, but even such supposedly-liberal bastions as the New York Times. Maybe lots of big corporations took advantage of the fake narrative to make unpopular business decisions they were planning on making anyway. And maybe ordinary San Franciscans, confronted with everyone telling them they were in a shoplifting epidemic, started paying more attention to security guards and petty criminals who had always been there, a sort of mass hallucination that gripped everyone in the city. I can’t rule this out. Americans thought crime was rising all throughout the early 2000s, when it was in fact way down. Or maybe some statistics that we already know are off by several orders of magnitude got off by an additional factor of two or so. I think this one is more likely, but I’m genuinely not sure.

- If they do it with perfect rationalist virtue, it tends to look like a long list of contradictory studies and statistics. The media says “every human being who has ever lived except for Hitler agrees that Housing First solves all problems!” Suppose you write a book saying something like “actually, five studies say Housing First had a small positive effect on this problem, three studies say it had a small negative effect, and two studies say it was neutral”. The average citizen reads the media and concludes Housing First is perfect and amazing, then reads you and concludes that something something studies whatever. In the end they settle on something like “it’s perfect and amazing, but there’s some kind of asterisk after this and maybe more studies are needed”. If you want to actually shake them out of the propaganda, you need to go further and declare confidently that Housing First is actually bad. Michael Shellenberger does this, and in a moment I’ll blame him, but I want to stress that he’s less bad than the mainstream media he’s criticizing. He is taking swings at an omnipresent orthodoxy of creepily consistent spin and bias, while also sometimes stretching the truth himself. So now, having given all those caveats - this book is not a good guide to the truth on complicated social science questions. It avoids actual lies, while presenting one side of a two-sided case, sometimes so much so that I feel comfortable characterizing it as misrepresentation. As long as there are two scientists in the world who agree with San Fransicko, it’s “Here’s what scientists say…”. If there is one statistic that supports a point and five that oppose it, you can guess which one the book brings up.

- I still feel conflicted on this without really being able to verbalize why. Maybe something like: these are profound psychological truths, but their failure mode is to be reduced to preachiness and haranguing. And in a book called San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities, there’s almost no way not to have them sound like preachiness and haranguing. It’s like how calling out injustice and highlighting the cruelty of those who ignore the less fortunate is all nice and well when Victor Hugo does it - but if the book is by Rachel Maddow, I am just going to skip those parts.

- I’m even more torn on the other civil rights question the book confronts, whether homeless people who don’t like shelters should be allowed to camp in tents. The libertarian reluctance to provide free health care has a very understandable justification: it wasn’t the government or the taxpayers who made you sick, so they have no obligation to make you healthy again. But ten thousand years ago , before there were governments or private property at all, anyone could sleep wherever they wanted, without having to work forty hour weeks to pay money to landlords, or limiting themselves to a few shelters. If the government bans people from sleeping on land, that’s making them worse than if the government didn’t exist at all; it’s a violation of their pre-existing rights. Some amount of this is unavoidable if you accept private property. But the idea that people can’t be anywhere at all, and must agree to be warehoused in a crowded and unpleasant shelter, seems like another, much higher level of imposition. The way I cut through both these problems is to have a high tolerance for people doing what they want, but a low tolerance for them impinging on the rights of others. I’m fine with a compromise where people can camp on public land, but if they start harassing people or piling up trash, the government can take action. This probably means Shellenberger and I agree on most real-world cases, but I remain invested in the tiny sliver of moral difference between our positions.

- The average person isn’t victimized by crime very often. There are about 1000 robberies a year in San Francisco (I think this is like mugging?), and another 1000 assaults. There are about 7000 homeless people - not all of them are criminals or addicts, but presumably there are a lot of criminals/addicts with houses, so let’s say a total of 20,000 people in this group. For the sake of argument, stricter policies will make half of them find God, and the other half will need to be forced into shelters/prisons/hospitals. And for the sake of argument, let’s say this ends all violent crime in San Francisco. You’d be institutionalizing 10,000 people a year, to prevent 2000 violent crimes a year. Even accepting that violent crimes are traumatizing and really bad, this doesn’t seem very utilitarian - being the victim of a violent crime would have to be 5x as bad as being forced to spend a year in an institution.

- Maybe this is thinking about it wrong. Being in crime-filled scary ghettos really negatively affects people’s quality of life. If “cleaning up the city” removed half of the quality-of-life difference between poor neighborhoods and rich neighborhoods, that would be a really big deal for a lot of poor people. I think this would matter a lot - that most of the damage from urban dysfunction isn’t overt crime. It’s litter, graffiti, literal broken windows, parks that smell like marijuana and are strewn with used needles. People blasting loud music in public places or residential streets at all hours of the night. People staying away from mass transit transportation or public parks or any public spaces at all because they know they’ll be yelled at and harassed or just have to deal with a low-grade miasma of disgust over everything, preventing a real Jane-Jacobs-style civic life from ever taking shape. Class segregation, because anyone who can get out of the dysfunctional areas is desperate to do that. The fall of civic pride, because cities get hard to be proud of. If there are 100,000 San Franciscans who live in bad areas, and “cleaning up the cities” improved their quality of life 10%, and institutionalization lowers 10,000 people’s quality of life by 50%, that could . . . potentially work out? (I think the big assumption here that worries me the most is that homeless/hardened criminals/addicts are responsible for most of the noise/litter/graffiti/minor crime/quality-of-life decrease, as opposed to just ordinary people who are jerks. I’m not sure how much institutionalizing the worst 10,000 people would or wouldn’t improve the inner cities.)

The Whole City Is Center by Slatestarcodex

- I’ve been told that we love kittens based on a misfiring of our evolutionary urge to love children. Should I abandon that one? I’ve been told I love beauty and nature and high mountains and deep forests based on evolutionary heuristics about what kind of places will have a good food supply – now that I can order take-out, should I ditch that too? Huge chunks of our hopes and dreams are the godshatter of misfired-evolutionary processes. Tell me what principled decision lets us judge among them, rejecting one as evil but the other as good?

- all I am saying is to be understanding. They’re not people who are coming from some sort of alien ideology of suffering being good for its own sake. They’re people who are taking the same godshatter you are, and applying a different process of arbitrary reflective equilibrium to it, in a world where none of us really understand or control the process of reflective equlibrium we go through. That gives me a different and more understanding perspective on them. It may not make me agree with them, but it makes me more willing to think of them as an odd but sympathetic potential-negotiating-partner rather than some sort of hostile villain.

- There is a sense in which you’re right, and a sense in which I’m right. Words both convey useful information, and shape our connotations and perceptions. While we can’t completely ignore the latter role, it’s also dangerous to posit fundamental value differences between people who use words one way and people who use them another. My concern is that I’ve seen people say “I am the kind of person who doesn’t believe in laziness, or in punishment, or in judging others. But that guy over there accuses people of being lazy, wants people to suffer, and does judge others. Clearly we have fundamental value differences and must be enemies.” All I’m trying to do is say that those people may have differing factual beliefs on how to balance the information-bearing-content of words versus their potential connotations. If we understand the degree to which other people’s differences from us are based on factual rather than fundamental value differences, we can be humbler and more understanding when we have to interact with them.

The Midwit Trap by philo.substack

Why are we so dismissive of simple solutions?

- Conflating smart with complex

- We assume that a complex solution is likely to be the product of more sophisticated and nuanced reasoning than a simple solution, and thus more likely to be correct. This is far from true.

- If we accept that a “midwit” is a real type of person, then it is the midwit that will be most vulnerable to this particular logical fallacy, because it targets their insecurity about their intelligence and because they will fail to recognize it. An intelligent person will know that there is no correlation between the simplicity of a solution and the sophistication of the reasoning that led to it

- The Pareto Principle

- The typical midwit rhetorical strategy is to present all of the causes without also presenting which causes account for what share of the consequences, falsely implying that all causes are equally important. Consider a statement like: “Airbnbs and speculators are among the causes of high rents.” This is a technically true statement, but presented in a way that is intended to lead the reader to a false conclusion, such as “Shark attacks are a growing cause of death in Maine.”

- It is not clear what the main culprit is here. It could be motivated reasoning, or it could be that we do not encounter the Pareto principle much in our everyday lives and fail to look for it. Nevertheless, failure to recognize the pervasiveness of the Pareto principle is a common factor in incorrectly rejecting simple solutions to complicated problems.

- Theory of Constraints

- One critical feature of a chain is that it is only as good as its weakest link…For such a system, total output is always dictated by the biggest bottleneck at any given time. You can only increase output by addressing the specific bottleneck that is constraining the whole system at any given time.

- We don’t encounter this issue as much in our everyday lives because we usually have access to lots of substitutes; if the road we usually take to work is closed, we can take an alternate route.

- The Theory of Constraints is a good example of how we are surrounded by complicated systems where the optimal strategy, by definition, is always a simple one: in this case, attack the biggest constraint.

- The Divide by Zero Problem

- Some solutions rely on convoluted chains of logic that are strictly dependent on every single statement being true. They are more likely to have hidden “divide by zero” problems that may be easily noticeable to the experienced practitioner but are invisible to the layman. Simple solutions might have errors too, but they will be much more obvious. Also, complicated chains of logic “feel” correct because a lot of the steps will be verifiably true; people sometimes forget that all of the steps have to be true for the entire argument to have any truth.

- Complicated stories seem more likely to be logically sound to a midwit, but simple strategies are actually far less likely to have hidden land mines.

Here is a version of a classic math puzzle:

a = bab = a²ab - b² = a² - b²b(a - b) = (a + b)(a - b)b = a + bb = 2b1 = 2

Every step of this seems correct at first glance. And yet, it doesn’t seem right that 1 = 2.

The trick is that in the fourth step, you divide both sides by (a - b), and we established in the beginning that a - b = 0. Since you can’t divide by zero, the whole statement is invalid.

- We Share 99% of our DNA with Chimpanzees

- In business, as in biology, sometimes it is just the 1% that is different that matters, and you can ignore the 99% that is the same. It doesn’t matter if we share 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees, because the difference is all in the 1%.

- people get hung up on the idea that two products need to be drastically different to generate meaningfully different outcomes. If a new product is 99% similar to an existing product X, people immediately exclaim: “X. You invented X.” In our ride-hailing example, skeptics make much of the fact that ride-hailing is mostly the same as taxis, and devote much attention to proving this; they both use drivers, cars, fuel, etc. The difference is in using software to manage dispatch and improve the user experience. No one denies the other 99% is the same; in fact, that is a key selling point!

- the incorrect heuristic here is to assume that making a small change in one part of a complicated system cannot have a huge impact on the output. How can restricting construction in a few cities drive up rents nationwide? How can reducing management and trading costs have such a big impact on total return? Once you understand that a small change can have an outsized impact, it is easy to see that a simple solution will often be more effective than a complex one.

Summary:

In Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Nicholas Taleb introduced the idea of Mediocristan and Extremistan. In Mediocristan, everything is normally distributed, and extreme events rarely happen. In Extremistan, there is an exponential distribution and extreme events happen much more often.

The Midwit Trap is to some extent just an application of Extremistan. The effectiveness of a simple solution depends on having a problem where one cause is responsible for most or all of the negative consequences. This is likely to be the case where there is a power law distribution or strict dependencies, but not so much elsewhere. We are used to solving problems in Mediocristan, where we usually cannot achieve a significant outcome with “one simple trick!” and so we are dismissive of simple solutions or simple explanations.

The Midwit Meme turns out to have a useful purpose, to remind us in a concise, memorable way that we cannot accept complicated solutions or explanations only because they feel smarter than a simple solution.

- Beware What Sounds Insightful by Cedric Chin

- Ads Don’t Work That Way By Kevin Simler

- Original Position (Wikipedia)

- Do I Deserve What I Have by Russ Roberts

- Acceptance Parenting by Agnes Callard

- The Myth of the Secret Genius by Brian Klass

- This Is Why You Shouldn’t Humor Woo Woo by Freddie deBoer

- Why I Changed My Mind About The Caster Semenya Case by David Epstein

- You're Probably Using The Wrong Dictionary by J Somers

- The Most Interesting Thing I’ve Ever Read by Tom Morgan

- Uncle, You Don’t Make Sense by Dinesh Raju

- Why speculate? by Michael Crichton

How Should We Feel About ADHD by Freddie de Boer

Whatever the origins, I can tell you that the people who just want to treat a potentially maddening medical condition are being badly served by those who want to have a doctor write an identity on a prescription pad.

Everything in Your Fridge Causes and Prevents Cancer by David Epstein

It wasn’t every sauna enthusiast who reaped the supposed protective effect against dementia; it was specifically those who used a sauna 9-12 times a month. Sauna bathers who hit the wooden bench 5-8 times a month — sorry, no effect. And those who went more than 12 times a month — again, no luck.

That should raise a caution flag in your head. When only a very specific subpopulation in a study experiences a benefit, it may indeed be that there is some extremely nuanced sweet spot. But it is more likely that the researchers collected a lot of data, which in turn allowed them to analyze many different correlations between sauna use and dementia; the more different analyses they can do, the more likely some of those analyses will generate false positives, just by statistical chance. And then, of course, those titillating positive results are the ones that end up at the top of the paper, and in the press release.

Here’s the point I want to hammer home: when you see a tantalizing health headline — like that saunas prevent dementia — keep an eye out for indications that the effect only applies to specific subgroups of the study population. Even if the headline is very authoritative, revealing nuggets are often buried lower in the story.

I want to stress that you shouldn’t assume the sauna results can’t possibly be true. But when you see Bears-undefeated-in-alternate-jerseys type conclusions — and someone is claiming one thing causes the other — you should hold out for more evidence.

Epstein also describes how “pre-registration” is used to combat multiple comparisons, data mining, and the high degree of freedom researchers have which when combined with bad incentives lead to the trope that “studies show...” is almost always a phrase followed by bs.

Education Doesn’t Work 2.0 by Freddie deBoer

- Relative position is mostly fixed even if on an absolute basis learning happens

- The present study shows that individual differences in educational achievement are highly stable across the years of compulsory schooling from primary through secondary school. Children who do well at the beginning of primary school also tend to do well at the end of compulsory education for much the same reasons. This is the finding of all such research.

- The kids in the top reading group at age 8 are probably going to college. The kids in the bottom reading group probably aren’t. This offends people’s sense of freedom and justice, but it is the reality in which we live.

- Within a cohort such as race, variation comes from an individual intrinsic qualities. Environmental reasons explain variation between cohorts

- absolute learning can happen. Formal education in and of itself does have durable and real improvements to intelligence. (The child care function of public schooling has also been transformative and progressive.) Doesn’t that disprove the point of this piece? Look at learning loss from Covid. Doesn’t that prove education works? Not in the sense I mean, no. Again, the question is not whether schooling helps individuals gain absolute knowledge or skills, but whether it can close relative gaps. If school works generically well across ability levels, it can’t. Formal education has real benefits. The trouble is that most everybody goes to school and enjoys those benefits, so the power of schooling to establish durable changes in relative position on the ability spectrum is limited. (And lower-performing people self-select out of higher education, which accelerates their being left behind.)

- And, yes, to repeat myself, absolute learning can happen. Formal education in and of itself does have durable and real improvements to intelligence. (The child care function of public schooling has also been transformative and progressive.) Doesn’t that disprove the point of this piece? Look at learning loss from Covid. Doesn’t that prove education works? Not in the sense I mean, no. Again, the question is not whether schooling helps individuals gain absolute knowledge or skills, but whether it can close relative gaps. If school works generically well across ability levels, it can’t. Formal education has real benefits. The trouble is that most everybody goes to school and enjoys those benefits, so the power of schooling to establish durable changes in relative position on the ability spectrum is limited. (And lower-performing people self-select out of higher education, which accelerates their being left behind.) Compulsory education is a double-edged sword if you’re interested in shaking up who’s on top and who’s on the bottom. As I suggested above, if you were really maniacally focused on closing relative gaps, you’d just prevent the higher achievers from attending school at all.

- Have a meaningful influence on academic outcomes where so many others have failed

- Be reliable, replicable, and scalable to a vast degree

- Cost little enough that the administration of this intervention is economically and politically feasible

- Somehow apply only to the students who are struggling or any subset thereof, and not to the students who are already flourishing, or else allow for us to prevent the parents of flourishing students from accessing this intervention for their own kids, lest we merely advance the whole student population forward but preserve the current relative distribution that determines professional and monetary rewards under meritocracy.

All of this suggests that there is something innate or inherent to academic ability. (Which again does not necessarily imply that this factor is genetic.) Many will reply to this essay by saying that just because something is innate does not mean that it is unchangeable. This is true, and I haven’t and wouldn’t say educational outcomes are permanently immutable. The question is, what can we do from the perspective of the system that would work to “fix our schools,” to achieve the (remarkably vague) education-driven social outcomes politicians and policy types want? How would we close the gaps?

The kind of intervention we would need has to

Simple.

I quote James Heckman, the same James Heckman who co-authored the Denmark paper and the problematic pre-K health outcomes paper. Ten years ago he wrote

Gaps arise early and persist. Schools do little to budge these gaps even though the [perceived -ed.] quality of schooling attended varies greatly across social classes…. Gaps in test scores classified by social and economic status of the family emerge at early ages, before schooling starts, and they persist. Similar gaps emerge and persist in indices of soft skills classified by social and economic status. Again, schooling does little to widen or narrow these gaps.

I would argue that, in the years since, the evidence that academic hierarchies are essentially static has only grown.

I will not attempt to spell out the political and policy repercussions of this reality here. The Cult of Smart is a book-length version of this argument that includes long sections describing both more practical educational reforms and broader society-level changes that could better protect those who are on the bottom of the academic performance spectrum. You may disagree with some or all of those proposals as you like. But they are an honest attempt to wrestle with a basic reality of education and society that politicians and wonks are not allowed to address plainly because of misguided fears about the consequences of this thinking. The evidence is clear: immense efforts in educational interventions have utterly failed to close performance gaps, and vast expenditures in education have failed to close socioeconomic gaps. It’s time to try dramatically different approaches, and it’s time to demand that people in the policy world accept reality.

Education is a good in and of itself, but the impact of education on the economy will always be most salient in political debates. By some metrics, the fastest-growing occupation in America is not programmer or microbiologist but home health aid. The job doesn’t require a college education. The median wage is $27,000 a year. Our system’s message to all of those people who will spend their days helping keep our elderly alive for poverty wages is, well, hey. Should have done better in school. Maybe the first step in doing better for them is recognizing that most of them never had a choice. But if you’re really dead set on education as the key to improving the economic fortunes of the disadvantaged, and you don’t think we can or should redistribute our way to a more just and equal society, and you’re fixated on moving kids from the bottom of the academic performance spectrum to the top, what can we do? What works? Nothing

Hard Work For My Kid, Not for Yours by Freddie deBoer

But there’s something profoundly disquieting about the vast divide between the political ideals articulated by our liberal educated class and the way they live their own lives, the way they teach their children to live theirs. In any other context, white people conspiring to deny children of color the same tools that they used to succeed themselves would be seen as flatly racist. Wouldn’t it?

Yes, we must recognize that we are dealt unequal hands in life, and advocate for using political tools to help account for this inequality. We could all stand to be more aware of the influence of structures of oppression and chance in our lives. But there’ no conflict between doing so and teaching our children to maximize their position within the broken old system while we labor to build the new. Even if we each have a certain level of potential in any given field, we can rise to meet that potential or not based in part on our environment and yes, our choices. To which degree, who can say? None of us knows the degree to which we are really in control of our destiny. But maybe we should ask ourselves how we might be hurting the futures of underprivileged children when we convince them that they have no control over theirs.

Pairs well with the Success Paradox:

I Can Tolerate Anything Except The Outgroup by Slatestarcodex

We started by asking: millions of people are conspicuously praising every outgroup they can think of, while conspicuously condemning their own in-group. This seems contrary to what we know about social psychology. What’s up? We noted that outgroups are rarely literally “the group most different from you”, and in fact far more likely to be groups very similar to you sharing almost all your characteristics and living in the same area. We then noted that although liberals and conservatives live in the same area, they might as well be two totally different countries or universe as far as level of interaction were concerned.

Research suggests Blue Tribe / Red Tribe prejudice to be much stronger than better-known types of prejudice like racism…Spending your entire life insulting the other tribe and talking about how terrible they are makes you look, well, tribalistic. It is definitely not high class. So when members of the Blue Tribe decide to dedicate their entire life to yelling about how terrible the Red Tribe is, they make sure that instead of saying “the Red Tribe”, they say “America”, or “white people”, or “straight white men”. That way it’s humble self-criticism. . They are so interested in justice that they are willing to critique their own beloved side much as it pains them to do so.

So how virtuous, how noble the Blue Tribe! Perfectly tolerant of all of the different groups that just so happen to be allied with them, never intolerant unless it happen to be against intolerance itself. Never stooping to engage in petty tribal conflict like that awful Red Tribe, but always nobly criticizing their own culture and striving to make it better! Sorry. But I hope this is at least a little convincing. The weird dynamic of outgroup-philia and ingroup-phobia isn’t anything of the sort. It’s just good old-fashioned in-group-favoritism and outgroup bashing, a little more sophisticated and a little more sneaky.

I can think of criticisms of my own tribe. Important criticisms, true ones. But the thought of writing them makes my blood boil. If you think you’re criticizing your own tribe, and your blood is not at that temperature, consider the possibility that you aren’t. But if I want Self-Criticism Virtue Points, criticizing the Grey Tribe is the only honest way to get them. The best thing that could happen to this post is that it makes a lot of people, especially myself, figure out how to be more tolerant. Not in the “of course I’m tolerant, why shouldn’t I be?” sense of the Emperor in Part I. But in the sense of “being tolerant makes me see red, makes me sweat blood, but darn it I am going to be tolerant anyway

.”

- Gwern bit about being against witches is easy if you don't believe in witches.

- CS Lewis quote CS Lewis: You would not call a man humane for ceasing to set mousetraps if he did so because he believed there were no mice in the house.

An Interview with Daniel Coyle, author of The Culture Playbook by David Epstein

Ice Breakers

All our lives, we’re taught that you have to build up trust before you can be vulnerable. Icebreakers are proof that we’ve got it exactly backwards. Moments of vulnerability, when shared, ignite connection.

- “Fear in a Hat” exercise: a group of incoming students write down their fears anonymously on slips of paper, and then take turns pulling each fear out and reading them aloud.

- 4 Hs Exercies: In groups of 4-6, and ask everybody to take a few minutes to reflect silently on four questions: 1) Who is your biggest hero? 2) What was your biggest heartbreak? 3) What is your family history? 4) What is your hope for the coming year?

“Belonging cues” are the connective tissue for the group brain

You know that warm, energizing feeling you get when you’re in a good group? That buzz of connection, creativity, and possibility? What you’re actually feeling is psychological safety. And psychological safety doesn’t just happen — it’s built through the continual exchange of belonging cues. Belonging cues are small, repeated behaviors that send a clear signal: You matter. I hear you. We care. We share a future. [This is an important precursor to honest debate or what Todd Simkin called a culture of truth-seeking]

Safety is not about wrapping people in fleece and making them comfortable. Rather it’s about creating conditions where you can be uncomfortable together. Where minority viewpoints are unafraid to speak up and be heard. So on a deeper level it’s really about curiosity and humility. In great groups, people aren’t behaving like rugged individualists; to the contrary, they’re always looking for opportunities to give and receive help.

Great cultures actually contain more tension. Because people aren’t afraid to disagree, to argue energetically about big issues — then go out for a beer. Because the relationships are strong enough to explore hard problems together. In weak cultures, you get what I call Smoothness Disease — that tendency to want to pretend that everything is good. To walk past disagreements. To pretend that everything is good when it really isn’t.

The feeling of being in a great culture isn’t smoothness — it’s the feeling of solving hard problems with people you admire. That’s a special feeling, and it’s the reason that people inside great cultures love it so much.

Remote Work

No silver bullet but some ideas:

- Toggling approach: alternate between remote and in-person, treating in-person work as a booster shot. Toggling keeps the relationships real.

- Bucketing: Divide your work into two buckets: productive and creative. For productive work, it’s fine to work remotely. After all, you’re just cranking away. For creative work, however, studies show that it’s more effective to be in person.

The most magical culture-building words ever invented: TELL ME MORE

When a colleague brings you a problem resist that overwhelming temptation to add value, to share wisdom, to fix things. Then, say the most magical culture-building words ever invented: TELL ME MORE.

Why Rational People Polarize by Kevin Dorst

- U.S. politics is beset by increasing polarization. Ideological clustering is common; partisan antipathy is increasing; extremity is becoming the norm (Dimock et al. 2014). This poses a serious collective problem. Why is it happening? There are two common strands of explanation.

- Psychological: confirmation bias

- Sociological: the modern information age has made it easier for people to fall into echo chambers

- So we have two strands of explanation for the rise of American polarization. We need both. The psychological strand on its own is not enough: in its reliance on fully general reasoning tendencies, it cannot explain what has changed, leading to the recent rise of polarization. But neither is the sociological strand enough: informational traps are only dangerous for those susceptible to them. Imagine a group of people who were completely impartial in searching for new information, in weighing conflicting studies, in assessing the opinions of their peers, etc. The modern internet wouldn’t force them to end up in echo chambers or filter bubbles—in fact, with its unlimited access to information, it would free them to form opinions based on ever more diverse and impartial bodies of evidence.

- I disagree with the claim that these “reasoning biases” are biases. Rather: I’ll argue that these tendencies—to interpret conflicting evidence as confirmatory; to search for confirming arguments; and to react to discussion by becoming more extreme—may be the result of fully rational processes.

- The distinction between the explanation is important because it leads to different remedies. Consider an example of the psychological explanation vs the sociolocial one:

- The psychological explanation is due to individual failings: each of us would have a better outcome if we unilaterally ate better—we are irrational to overeat. Thus the collectively bad outcome “filters up” from suboptimal choices of the individuals. Call this an individual problem.

- In contrast, the bad outcome in Case 2 is due to structural failings. None of us could get a better outcome by unilaterally changing our decision—we are rational to overfish. The problem is that we are caught in a tragedy of the commons. To put it bluntly: individual problems arise because people are dumb; structural problems arise because people are smart. You solve an individual problem by getting people to make better choices…You solve a structural problem by changing the choices they face. As commonly articulated, the standard story represents polarization as an individual problem: it implies that polarization arises, ultimately, from irrational informational choices on behalf of individuals. It therefore predicts that the solution will require teaching people to make better ones. Educate them; inform them; improve them. If I’m right, this is a mistake. The informational choices that drive polarization are not irrational or suboptimal. Like the tragedy of the commons, polarization is a structural problem. It arises because people are exquisitely sensitive to the informational problems they face—because they are smart. It doesn’t require educating them; it requires altering the choices they face.

Case 1: We face a heart disease epidemic—we would all be better off if we all ate better.

Case 2: Our fisheries are being depleted—we would all be better off it we all fished less.

- 3 rational tendencies:

- Biased assimilation: People tend to interpret conflicting evidence as supporting their prior beliefs (Lord et al. 1979)

- Confirmation bias: People tend to seek out new arguments that confirm their prior beliefs (Nickerson 1998).

- Group polarization: When people discuss their opinions in groups, their opinions tend to become more extreme in the direction of the group’s initial inclination (Myers and Lamm 1976).

- How could these tendencies be rational? The answer I’ll give relies on three epistemological facts:

- Some types of evidence are more ambiguous than others: it is harder (even for rational people) to know the rational way to react to them.

- The more ambiguous a piece of evidence is, the weaker it is: if you should be quite unsure how you should react to a piece of evidence, then that evidence shouldn’t lead to a radical shift in your opinion.

- Some information-gathering strategies will predictably yield more ambiguous (hence weaker) evidence than others.

- Fact #3 is the key: If you are presented an ambiguous claim (like most claims are: ie does lowering interest rates create inflation?) you may try to de-bunk it. This is hard and debunking attempts usually don’t resolve to unambiguous evidence. : Since rational people try to get the strongest evidence possible, you should try to debunk the one that you think you’re most likely to succeed at de- bunking. Which one is that? The one that tells against your belief, of course! (You have reason to think that evidence against your belief is more likely to be misleading than evidence in its favor—otherwise you wouldn’t believe it!) Upshot: if you’re sensitive to evidential ambiguity, then when presented with conflicting studies it is rational—other things equal—to try to debunk the one that conflicts with your prior beliefs.

- Our psychological biases are rational:

- Biased assimilation—people’s tendency to interpret conflicting evidence as supporting their prior beliefs. The empirical regularity appears to be due to the fact that people spend more energy trying to debunk the piece of evidence that tells against their prior opinions than the piece tells in favor of them (Lord et al. 1979; Kelly 2008).

- Confirmation bias—people’s tendency to seek out new arguments that confirm their prior beliefs. That is, if people are given a choice of which slant of argument to hear (or—what comes to the same thing—which news source to watch), they will tend to choose the one that agrees with their opinion. This should sound familiar: it is precisely the strategy I argued is rational in the context of argument assessment. Hearing a good argument results in less ambiguity than hearing a bad one. A rational person who’s interested in the truth should be trying to get strong evidence, and so to avoid ambiguity. That means—other things equal—they should prefer hearing arguments that they expect to be good, rather than those they expect to be bad. And, in general, they should expect arguments that agree with their beliefs to be better than those that disagree with them. So rational people exhibit confirmation bias.

- Group polarization—the tendency for a group’s opinion to become more extreme after discussion, in the same direction as the group’s initial tendency…in our political context it’s common knowledge that loads of people agree with your views and loads of people disagree with them. So shouldn’t these conflicting bits of evidence balance out? No—for we’re back in our exploring-explanations scenario. You’re presented with two pieces of conflicting evidence: these people all agree with your belief; but these people all disagree with it. When you have conflicting evidence and other things are equal, what’s the rational thing to do? Spend more energy debunking the evidence that conflicts with your prior beliefs! It’s therefore rational to spend time coming up with alternative explanations for why your political opponents disagree with you—and thus (upon coming up with such explanations) rational to give more weight to the political opinions of those who agree with you. So rational people also exhibit group polarization.

- We face a structural problem: the modern internet has created a social-informational situation in which optimal individual choices give rise to suboptimal collective outcomes. If this is right, we should think of political polarization less as a health epidemic and more as a tragedy of the commons. That means two things. First, it means focusing less on changing the choices people make, and more on changing the options they’re given. And second, it means recognizing just how smart the “other side” is: that those who disagree with you may do so for reasons that are subtly—exquisitely—rational.

Invisible Hands and Infinite Money by MarginalCall

- Successful narratives capitalize on two critical psychological traits in people’s values scale: understanding human’s desire a fair game & and desire for self-determination. People might say they value equality but in practice its not what they really want—people want fair games with winners and losers. They want somebody to win, they want to like the winners, and they want to be like the winners. But they want the challengers to have a shot, and they want them to be able to play again.

- We can create a pretty simple psychological model to see how this works in action with just a few parameters. Humans need to feel special, humans desire freedom and fairness, and humans fear their own mortality. From the fear category we can divide them into two groups on how they compensate for it: people driven by the desire to control things (cheat death), and people who are driven to experience as much as possible (maximize life). From here you can craft organizing narratives to pitch anyone, for good or ill.

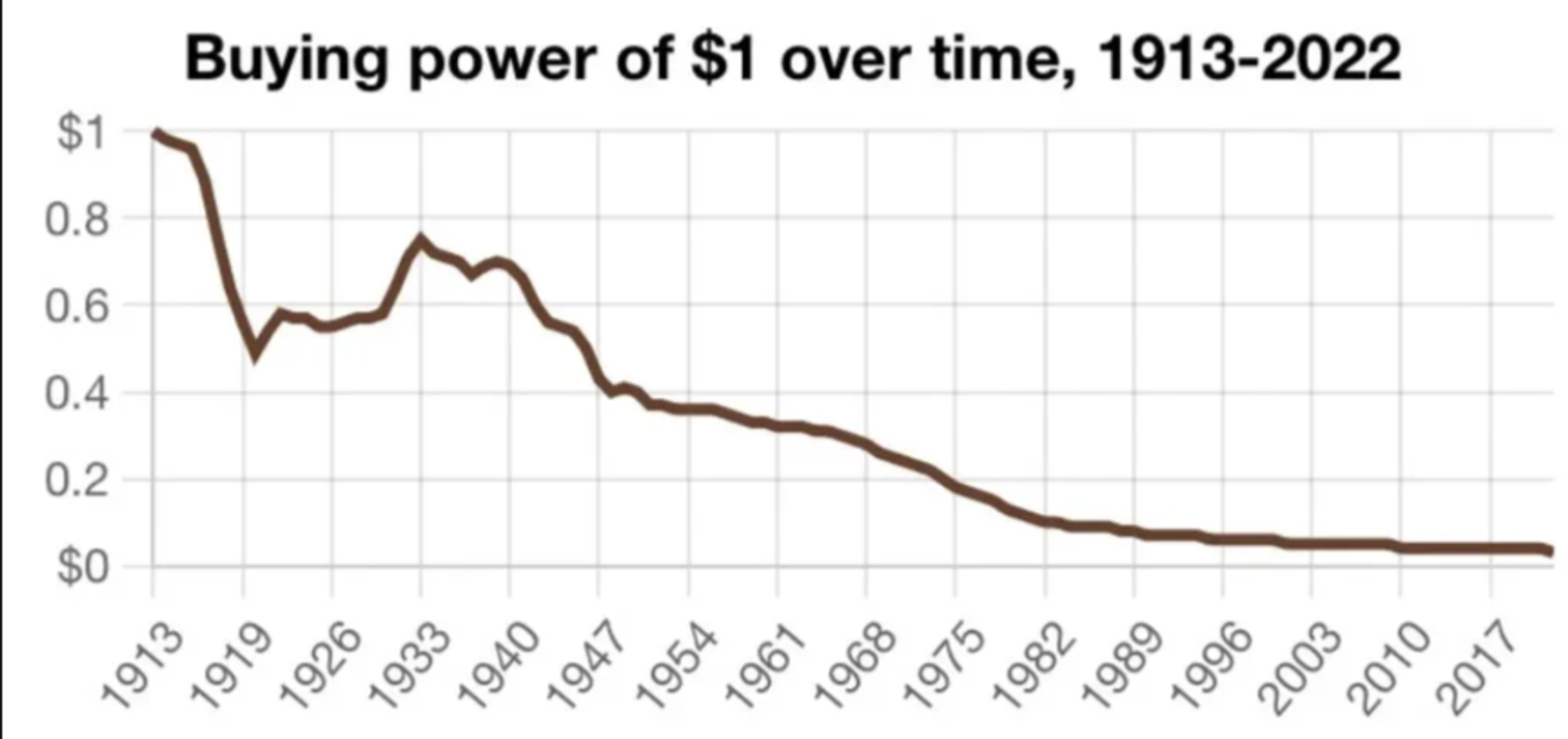

- [Me: The value of useful stuff things goes up over time relative to dollars is the conclusion you should draw from this. You should not be trying to think of how to make the dollar maintain its value. Inflation is a great tension because it has some sweet spot and too low or high is not good.

- The trick the chart is trying to play is using the fact that in real life and trade time is a one-way ticket to hide that the value of things can flow both ways on the time axis. Additionaly, not only is the relationship between value and price psychological—its not linear either. What say would sole capability to produce Intel Core 7s or iPhones worth in 1913? Everyone single one of those dollars and then some more at the very least.A dominant tech edge is worth infinite money and in periods of revolutionary tech development everybody is throwing money at it, chasing it—because it is not optional. What exactly do you think your saved money will be worth if the other guy gets infinite money? …That’s the infinite money game. Because what is tomorrow’s decisive edge in technology worth in today’s “money”? All of them. Participation is involuntary because it relies on other societies not playing. Narratives that fail to deliver any kind of edge in the technology game have zero infinite money value, require an environment of unreality and/or violence to both achieve and maintain network effects. Both religion and bitcoin reside in this category. On a geopolitical scale the winner of this game now decides not only what its own money is, but since you need to buy the tech—their money is also your money now too homie. It costs a lot of money to go against self-interested free forming coalitions lets examine the interplay between politics dictating markets. Because there is no invisible hand kicking political price exploration back inside the median, and it can cost very little money split coalitions and shift the entire market. This is about republicans of course. The republican organizing narrative is a manufactured narrative, not based on empirical evidence or best known practices, and is dominated by their sub-group of Christian fascists who are trying coalition break their way into the prevailing narrative position after having experienced decades of prevailing narrative share loss at the national level. Republicans present themselves as champions of the free market which is really just them trying to create the illusion that their preferred parameters include all the choices—while simultaneously enabling group elites to engage in unfair practices like pocketing externalities. But they most definitely are about establishing hard limits on what is considered acceptable trade based on their cultural values, which are based on thousands of years old myths. In their market you are free to be as Jesus-y as you wanna be. The culture wars are a reflection of this narrative decline, the money follows the herd, and when it comes to their tastes the herd is long gone. Nowhere is this more visible than the Merry Christmas vs. Happy Holidays and the red cups at Starbucks. Starbucks, in the business of selling you overpriced sugary drinks sometimes flavored with coffee, serves said drinks in non-descript red cups during the holiday season. They don’t say Merry Christmas on them to the chagrin of the Christian fascists. They established a whole sub “war on Christmas” narrative track over it that is naturally full of emotionally manipulative falsehoods while being spectacularly stupid at the same time. Starbucks of course has nothing against Christmas. And really, almost nobody is against Christmas; Christmas makes metric shit tons of money for everybody. Starbucks has just grown to a scale that they serve the broad market and they happen to have large numbers of Jewish customers, Muslim customers, and every other kind of customer. Starbucks wants all their customers to feel the holiday cheer and open up those wallets, which precludes serving Jewish folks $8 drinks in Merry Christmas cups. Starbucks, a group focused on maximizing profits does not want to carry the cost printing 5 different cups in every size which would then proceed to clog up all their service stations; making those profits possible. These decisions are not made because they’re woke. They’re not trying to drive the culture, they’re responding to it. Regular people see red cups and think holiday festivities, Christian fascists see red cups and see loss of status for the narrative they’ve tied their entire identity to and gave them a head full of spiders. Christmas is awesome, quit crying—you’re making it suck. We get a similar reactionary narrative against inclusive advertising, that companies are pushing culture that the white Christian male atop the republican hierarchy does not approve of. One need not look very far to find one of them ranting about plus size models in adverts (you are supposed to look good for him ladies). There is no “big fat” glamorizing obesity in fashion my angry little incel, there is zero incentive for it. They might be trying to create some socially conscious do no harm kind of brand image, but that is secondary to profit and they only hit the airwaves because plus size sales already justify the ad spend. Again, this is the market reacting to the herd, not driving it.

Anton Ego's Lesson (paywall) by Freddie deBoer

- should we cancel Pablo Picasso?…

- it’s not the role of artists and thinkers and scientists and creators to be morally impregnable people. It’s their role to do the very best they can at what they do. Of course they should be good people, in exactly the same way all of us should be, but it’s a category error to judge an artist’s art by your perception of their moral fiber

- desires for artistic satisfaction exist independently of the category of human moral apprehension. They just aren’t the same things. To ask about someone’s talent and reply with an argument about their morality is to be guilty of non sequitur.

- The truth is that moral behavior is both the most valuable and cheapest thing you can ask for in a human. Unlike being talented, being a good person is available to all of us. And while we’d all like to be surrounded by good people, we also intuitively understand that there’s nothing particularly novel or covetable about that status. This is the reason why you might meet the best person you’ve ever met in your life on the subway, the most moral and forgiving and humble and gentle, and take no notice, while if Kanye West brushed by you on the sidewalk, you’d tell all of your friends. You might say “that vicious anti-Semite, Kanye West,” but your very eagerness to share who you saw descends not from your apprehension of his moral worth but from your understanding that he’s a celebrity and that he became a celebrity because of his undeniably rare ability to create special music. Is any of this good? Is it healthy to chase talent and ability rather than compassion and manners? Again, it’s the wrong question. As a species we just do value great ability over moral considerations. We always have and we always will…the sweep of time is implicated, our sense that only certain kinds of acts are worthy of being remembered. Being a great friend doesn’t cut it. I freely acknowledge that this would be a better world if it did.

- Rarity is always rewarded. Picasso isn’t the most famous artist of the 20th century just because he produced great work but because he was so unreasonably gifted, his talents so casual and prodigious, his output so effortlessly virtuosic. It’s like what they say about the greatest athletes: they make it look easy. They do with grace that which most of us can’t do at all. And so the rest of us are left to try and enjoy life and to maintain the perspective that, on a long enough time frame, it all falls away. While we’re here on earth, though, we might take seriously what we already know, that talent isn’t fair, that we are limited from the day we are born, and that people will forgive anyone if they can cook a great meal or sing a good tune. That’s just who we are. Maybe we could stop writing essays where we pretend not to know it.

- (since moral tastes evolve over time, everyone will eventually be canceled, including today’s cancelers. Since ars longa and vita brevis, art will inevitably outlive the moral conditions under which it was created. Any minimally intelligent person can sort this out)

My Climate Posture -- Starting Assumptions for Talking About Climate by Venkatesh Rao

- Here, we have an unstable situation with both flow and stock aspects, developing rapidly in the direction of sudden worsening, with no strong technological driver spinning up as a balancing force with anywhere near sufficient rapidity (and it is no accident that the two examples I could think, whatever their benefits, both contributed to creating the climate problem). We are now close enough to the brink that even if a magical fusion-reactor technology were demonstrated tomorrow, deploying it at sufficient scale would take long enough that things would get worse before they got better.

- There are no plastic-straw marketing campaigns here that can meme the problem into not existing. No Joan-of-Arc figures like Greta Thunberg dominating headlines. No clean spreadsheet models and stock-flow diagrams that can be used by distant wonks to administer the problem out of existence with neat little taxation or interest rate knobs. No True Names like “degrowth”, “net zero” or “circular economy” that will magically dissolve the mess through sheer magical-rhetorical force. No monocausal “solutions” like “just deploy nuclear at scale.” The story of Kern county is what realistic climate action actually looks like in a real political arena full of powerful actors at odds with each other. The problem is complex. The solution, even when leveraged, strategic, and disruptive, is going to be irreducibly complex too. I tend to take as an article of faith the systems science rule of thumb that the complexity of solutions generally matches the complexity of the problems. If it doesn’t, then you either got lucky, or there are negative externalities you’re ignoring.

- The narrative web of the climate discourse is very hard to map, but one thing is clear: Almost everybody is an NPC in the current situation, and is primarily desperately solving for how not to feel like an NPC. This is an important point. Humans have a strong tendency to confuse a psychologically satisfying amount of agency with a materially effective amount. A broad culture of what we very-online people call cope rules everything around us when it comes to climate. It is a deep-rooted tendency, and an understandable one. Much as we might intellectually desire such laudable goals as the survival of almost everybody through a planetary crisis, our sense of meaningful existence is tied to individual agency. We’d rather stride grim-faced with a gun across a devastated post-apocalyptic landscape, masters of our own fates, than feel helpless within a world that’s largely doing fine and even providing for us. I’m no exception. The last thing I wrote publicly about climate, a 2015 essay in the Atlantic, arguing for a war-like economic mobilization, now feels hopelessly naive. A cope rooted in uncritical technocratic admiration for the grandeur of American economic mobilization during World War 2 Now that I have nearly a decade of consulting experience around climate and sustainability under my belt (and also, thanks to more reading and the experience of Covid, a better understanding of how “wartime economies” actually work), it is clear to me that that line of thought is basically a dead end. For normal-sized problems, such desperate attachment to felt agency is not an issue. In fact it is a critical feature. Generally a psychologically satisfying amount of agency is not too far off from a materially effective amount. The gap can be closed with a certain amount of gritting of teeth and acceptance of pain. Assuming reach and grasp are the same thing is how we humans Get Things Done. But the universe is not conveniently arranged to make all problems fall within reach of our gritted-teeth heroic grasping. Climate action is possibly one of those problems.

- There are dozens of copes in the theater market: Ban plastic straws, call your political representatives, vandalize paintings in museums, work on long-shot inventions which might make you rich, but will make no dent in the problem, work on wild-eyed carbon tax proposals outside of, and unaware of, the political processes they will eventually have to engage with. And then there is of course the all-time-favorite: “Raising public awareness.” We’re well past useless diminishing returns on this front, and possibly into negative returns — public awareness can at most create a climate of temporary acute pressure on political processes. Pressure that is highly vulnerable to capture by misguided charismatic causes and unreliable messiahs. I suspect we’re at a stage in the evolution of the problem where more awareness means more people acting with urgency to secure their own futures at the expense of others’ futures.

- I have a growing intuition that temporarily surrendering to a sense of helplessness in the face of complex problems, at least for a while, is the beginning of sanity. You can’t begin to acquire real agency until you learn to let go of comforting illusions of agency. And letting go requires accepting a liminal helplessness. The idea that a period of helplessness might be valuable, and even necessary, is deeply unpopular. The intuition underlying the thought only tends to be palatable if couched in religious terms. The AA 12-step program, for example, calls for declaring helplessness and surrendering to a higher power. The popular serenity prayer that often goes along with it lays it out, with a side of cope. But the thing about this prayer is that you’re not actually surrendering to a sense of helplessness. You’re surrendering to a sense that an inscrutable and benevolent higher power is going to take care of things if you do. You’re not surrendering so much as delegating upwards to a comforting fiction. I have a secondary intuition here, that any benefit of accepting helplessness for a while is entirely canceled out if it calls for an attitude of religious surrender. Any potential benefits are lost to the clouding effects of comforting fictions. Wherever in the world religion is still a powerful force, it is customary to view religious helplessness and surrender as somehow admirable, but a sense of atheistic helplessness as an absolute moral failing. To the religious mind, a surrender to anything other than a sense of the divine is the same thing as nihilism. The American version of this is particularly unique, since it is the only major country to combine third-world religiosity with first-world material conditions (though those conditions are getting increasingly fragile). The American way is to either cling to a delusional sense of sufficient agency regardless of the scope or nature of the problem, or turn to an aggressively religious helplessness. Two crude caricatures of this religious posture, from opposite ends of the political spectrum:

- The solution to every problem is to stock up on guns, turn to Jesus, and wait for the problem to turn into one you can shoot at.

- The solution to the problem is to repent for your complicity in structures of historical oppression, and it is your duty to suffer as much or more as others.

In both cases, you’ve not really embraced helplessness. Your “action” strategy is to put a spin of religious necessity on an anticipated course of unmanaged events that it would be morally wrong to resist, and wait for the current problem to turn into a problem you’ve prepared some ritual behaviors for (shooting things or self-flagellation).

The gun nut would be disappointed if the situation didn’t devolve into a shooting contest.

The hairshirt-green (Bruce Sterling came up with that term a decade ago) nut would be disappointed if the situation didn’t demand self-flagellation eventually.

The Toxoplasma Of Rage by Slatestarcodex

- PETA doesn’t shoot themselves in the foot because they’re stupid. They shoot themselves in the foot because they’re traveling up an incentive gradient that rewards them for doing so, even if it destroys their credibility.

- In the same way, publicizing how strongly you believe an accusation that is obviously true signals nothing…the more controversial something is, the more it gets talked about. A rape that obviously happened? Shove it in people’s face and they’ll admit it’s an outrage, just as they’ll admit factory farming is an outrage. But they’re not going to talk about it much. There are a zillion outrages every day, you’re going to need more than that to draw people out of their shells. On the other hand, the controversy over dubious rape allegations is exactly that – a controversy. People start screaming at each other about how they’re misogynist or misandrist or whatever, and Facebook feeds get filled up with hundreds of comments in all capital letters about how my ingroup is being persecuted by your ingroup. At each step, more and more people get triggered and upset. Some of those triggered people do emergency ego defense by reblogging articles about how the group that triggered them are terrible, triggering further people in a snowball effect that spreads the issue further with every iteration.

A while ago I wrote a post called Meditations on Moloch where I pointed out that in any complex multi-person system, the system acts according to its own chaotic incentives that don’t necessarily correspond to what any individual within the system wants.

A while back there was a minor scandal over JournoList, a private group where left-leaning journalists met and exchanged ideas. I think the conservative spin was “the secret conspiracy running the liberal media – revealed!” I wish they had been right. If there were a secret conspiracy running the liberal media, they could all decide they wanted to raise awareness of racist police brutality, pick the most clear-cut and sympathetic case, and make it non-stop news headlines for the next two months. Then everyone would agree it was indeed very brutal and racist, and something would get done.

But as it is, even if many journalists are interested in raising awareness of police brutality, given their total lack of coordination there’s not much they can do. An editor can publish a story on Eric Garner, but in the absence of a divisive hook, the only reason people will care about it is that caring about it is the right thing and helps people. But that’s “charity”, and we already know from my blog tags that charity doesn’t sell. A few people mumble something something deeply distressed, but neither black people nor white people get interested, in the “keep tuning to their local news channel to get the latest developments on the case” sense.

The idea of liberal strategists sitting down and choosing “a flagship case for the campaign against police brutality” is poppycock. Moloch – the abstracted spirit of discoordination and flailing response to incentives – will publicize whatever he feels like publicizing. And if they want viewers and ad money, the media will go along with him.

Which means that it’s not a coincidence that the worst possible flagship case for fighting police brutality and racism is the flagship case that we in fact got. It’s not a coincidence that the worst possible flagship cases for believing rape victims are the ones that end up going viral. It’s not a coincidence that the only time we ever hear about factory farming is when somebody’s doing something that makes us almost sympathetic to it. It’s not coincidence, it’s not even happenstance, it’s enemy action. Under Moloch, activists are irresistibly incentivized to dig their own graves. And the media is irresistibly incentivized to help them.

Lost is the ability to agree on simple things like fighting factory farming or rape. Lost is the ability to even talk about the things we all want. Ending corporate welfare. Ungerrymandering political districts. Defrocking pedophile priests. Stopping prison rape. Punishing government corruption and waste. Feeding starving children. Simplifying the tax code.

But also lost is our ability to treat each other with solidarity and respect.

Under Moloch, everyone is irresistibly incentivized to ignore the things that unite us in favor of forever picking at the things that divide us in exactly the way that is most likely to make them more divisive. Race relations are at historic lows not because white people and black people disagree on very much, but because the media absolutely worked its tuchus off to find the single issue that white people and black people disagreed over the most and ensure that it was the only issue anybody would talk about. Men’s rights activists and feminists hate each other not because there’s a huge divide in how people of different genders think, but because only the most extreme examples of either side will ever gain traction, and those only when they are framed as attacks on the other side.

People talk about the shift from old print-based journalism to the new world of social media and the sites adapted to serve it. These are fast, responsive, and only just beginning to discover the power of controversy. They are memetic evolution shot into hyperdrive, and the omega point is a well-tuned machine optimized to search the world for the most controversial and counterproductive issues, then make sure no one can talk about anything else. An engine that creates money by burning the few remaining shreds of cooperation, bipartisanship and social trust.

Imagine Moloch looking out over the expanse of the world, eagle-eyed for anything that can turn brother against brother and husband against wife. Finally he decides “YOU KNOW WHAT NOBODY HATES EACH OTHER ABOUT YET? BIRD-WATCHING. LET ME FIND SOME STORY THAT WILL MAKE PEOPLE HATE EACH OTHER OVER BIRD-WATCHING”. And the next day half the world’s newspaper headlines are “Has The Political Correctness Police Taken Over Bird-Watching?” and the other half are “Is Bird-Watching Racist?”. And then bird-watchers and non-bird-watchers and different sub-groups of bird-watchers hold vitriolic attacks on each other that feed back on each other in a vicious cycle for the next six months, and the whole thing ends in mutual death threats and another previously innocent activity turning into World War I style trench warfare.

I Think You Should Be Kind by Freddie deBoer

Ultimately, while there are penis-havers and vagina-havers, and this has relevance in certain domains such as in sexual partner selection, the basic empirical observation that has powered growing awareness of trans rights remains the most important thing: there are many people in the world whose felt, lived, intrinsic, internal, or otherwise experienced gender identity does not match with the sex category of their birth. This is, as I said, an empirical reality just as much as someone having a vagina or XX chromosomes is an empirical reality - whether you agree to abide by their gender self-identification or not, many people feel that identification with a gender other than that assumed by society. They exist whether you believe in them or not! And their gender identification is sufficiently inherent and powerful and passionate that they are willing to experience widespread stigma and the very real risk of violence in order to live in a way consonant with their identity. You remember the old “we’re here, we’re queer, get used to it” chant? The point of that chant was to draw attention to the fact that homosexual people existed, regardless of whether anyone approved of them or not; you could say that they didn’t deserve rights but you couldn’t make them disappear. The same point has to be underlined in the present moment: regardless of how you feel about them or your stance on various related controversies, there are millions of people who believe that they can’t live with the gender identity that society would once have forced on them.

And to speak in terms that American conservatives should respect, in a free society, how can these people be told that they can’t live the way they want to? Are people in a free society free to call themselves men, women, or other? The Constitution says that they are. Are people in a free society free to dress how they would like? They are. Are people in a free society free to enter into personal or romantic or sexual relationships with any adults that consent to being in those relationships? They are. Are people in a free society free to only associate with those who respect their gender identities? They are. Are those of us who are not trans free to respect the gender identities of trans people and call them by their preferred names and pronouns? We are. So what exactly is the beef, here? What do you have to do, if you accept these freedoms, other than to leave trans people alone? Again, you don’t have to like trans people or associate them, and they’re easy to avoid if that’s what you’ve made up your mind to do. And no, personally, I wouldn’t favor any law that required you to call them by their preferred gender identity, on free speech grounds. But then, you’re also free to say that I’m Tibetan; that you can say it does not will the falsehood into becoming the truth.

How many genders are there?!

I don’t know. I don’t care. Like, I don’t understand why this is an operative or important question. The vast majority of people who are trans-identifying identify as transmen and transwomen, and not misgendering them is simple. Some people identify as non-binary or gender queer. Do I fully understand this? Not really. Do I need to? No, as I’m someone who knows how to mind his own business. Simple human respect and basic manners compels me to call these people what they would like to be called. (I cannot stress this enough: it costs you nothing to respect someone else’s gender identity.) Are there some people out there, particularly on social media, who have more exotic gender definitions? Sure. Do I sometimes find that stuff a little silly? I guess so. But, again, since it costs me nothing to respect their gender identity - as in, I literally don’t have to do anything at all - I’m very happy to do so. I suspect a lot of those people will probably adopt a more conventional gender identity as they age, but if they don’t, again… who cares? It’s none of my business.

A Tale of Two Cycle Memes by Venkatesh Rao

The small problem with the idea is that it neglects all other archetypes of strength, most obviously feminine and nurturing ones. It emphasizes the strength of 300 hairless men with airbrushed sixpacks dying at Thermopylae over other dimensions of strength, such as forbearance, empathy, patience, doubt, and so on.

Instead of creating good times, strong men mostly seem to create dumb times. Times characterized by endless cycles of pointless violence that cause steady destruction and regression.

And instead of the idealized Strong Man of the memes, at best you mostly get what the British call the "hard man" -- the hard-drinking pub dweller willing to combatively take on all comers, and die on stupid hills for stupid causes. Or young bucks aspiring to acquire reputations as hard men. These are the kinds of men who would rather watch YouTube videos about the Roman empire when sober, and punch walls when drunk or high, than (to invoke a rather mean-spirited progressive meme), "go to therapy." The actually existing hard man, as opposed to the mythical strong man, seems to be driven by what a meditative friend of mine once poetically described as "myopic, selfish desperation." A variety of weak man.

But there is a more obliquely relevant progressive dual to the strong/weak cycle meme that operates by its own opposed kind of cartoon logic: Hurt people hurt people. The meme is generally deployed as a loftier cousin to the more combative who hurt you?